From late October and into November 2024, including the period of the Hindu festival Diwali, a thick, toxic smog has enveloped northern India and Pakistan.

Delhi, India

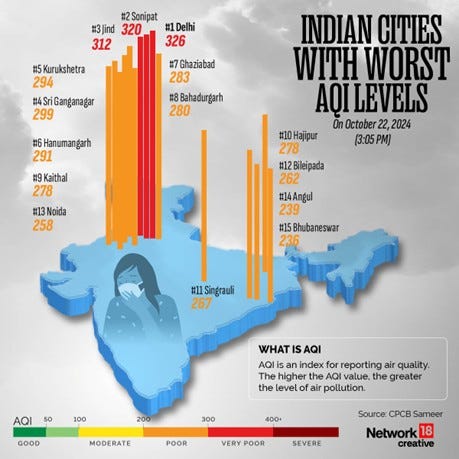

In Delhi, India’s capital city, air quality deteriorated to severe and extremely poor levels. Pollution levels rose to 65 times the World Health Organization (WHO)’s recommended safe limit at several locations in the city. Experts warned that the situation would worsen due to weather conditions, the use of firecrackers during the festival of Diwali, and burning of crop remains in neighbouring states (Figure 1).

Delhi is enveloped in a thick blanket of smog every winter due to smoke, dust, low wind speed, and vehicular emissions. The levels of tiny particulate matter (known as PM 2.5), which can enter deep into the lungs and cause a host of diseases, reached as high as 350 micrograms per cubic metre in some areas. Air quality is categorized as very poor when PM 2.5 levels reach 300 to 400, and it is termed severe when the level reaches 400-500.

On 18th November 2024, municipal authorities in the Indian capital declared an emergency as toxic smog overwhelmed the city. Schools were closed and people were urged to stay inside as the Air Quality Index (AQI), a measure of the concentration of fine particulate matter in the air, soared to 1,600.

Figure 1.

Lahore, Pakistan

In Lahore, severe air pollution conditions in Pakistan's second-largest city have led to over 900 hospital admissions in a single day, with children and the elderly being particularly affected by respiratory issues. In response, authorities instructed offices to operate at reduced on-site capacity, closed primary schools for a week, and implemented a green lock-down requiring 50% of employees to work from home. Additional restrictions include bans on unfiltered cooking grills, limits on motorised rickshaw use, and early closures for wedding halls.

Lahore's AQI reached over 1,000 for the first time since the monitoring group IQAir began keeping records.

From NASA….

Every November, satellites detect large numbers of small smoke plumes and heightened fire activity in northern India and Pakistan as farmers burn off excess straw after the rice harvest. Many farmers, particularly in the Punjab region, use fire as a fast, inexpensive way to clean up fields before planting winter wheat crops. The influx of smoke to the densely populated Indo-Gangetic Plain often contributes to a sharp deterioration of air quality in the autumn.

Smoke from crop fires is not the only contributor to the hazy skies. Influxes of dust sometimes arrive from the Thar Desert to the west. An array of other human-caused sources of air pollution in cities, including motor vehicle emissions, industrial and construction activity, fireworks, and fires for heating and cooking, also produce particulate matter.

Furthermore, temperature inversions are common in November and December as cold air rolls off the Tibetan Plateau and mixes with smoky air from the Indo-Gangetic Plain. An inversion allows warm air to trap pollutants near the surface. The low-hanging haze becomes hemmed in between the Himalayas to the north and the Vindhya Range to the south.

Figure 2. Satellite image (NASA)