America’s sinking east coast

A case study of isostatic readjustment, climate change and coastal flooding

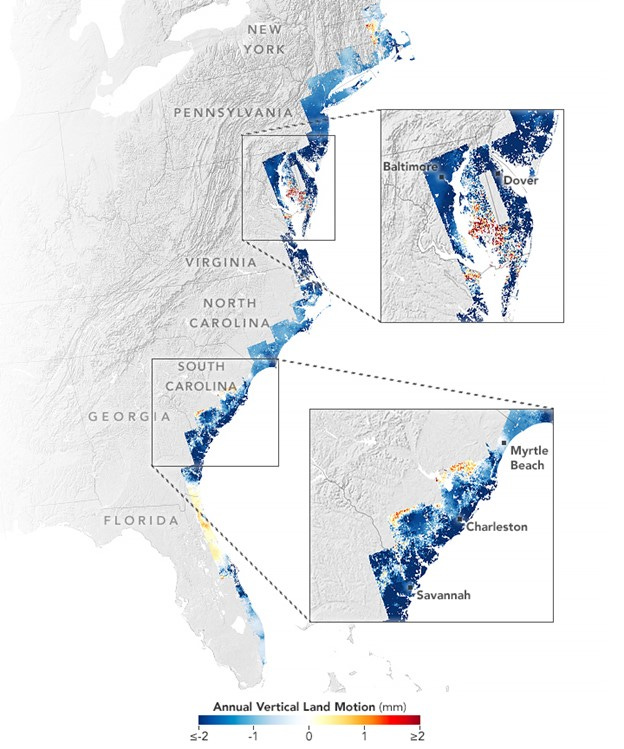

As we enter the season of hurricanes, which, although are not more frequent with climate change, are more likely to be more intense and damaging (as seen with Hurricane Beryl in July 2024), it is worth considering one of the coastlines most at risk. One synoptic factor that is important is the role of isostasy, or isostatic readjustment, on the east coast of the USA (Figure 1).

[Figure 1 highlights the variability in the rising and falling of land across much of the east coast. Areas shown in blue subsided between 2007 and 2020, with darker blue areas sinking the fastest. The areas shown in dark red rose the fastest.]

Figure 1. Vertical movement of the east coast of the USA

Along much of the U.S. east coast rising seas resulting from melting ice and the thermal expansion of warming water is only part of the problem threatening coastal areas. The land is also sinking. This is threatening infrastructure, farmland, and wetlands that millions of people along the coast rely upon.

In a recent study, researchers reported that more than half of the infrastructure in major cities such as New York and Baltimore is built on land that sank, or subsided, by 1 to 2mm per year between 2007 and 2020. Over 850,000 properties and critical infrastructure including several highways, railways, airports, dams, and levees were all subsiding.

The data also show that most East Coast marshes and wetlands - critical for protecting many cities from storm surge during hurricanes - were sinking by rates over 3mm per year. They found that at least 8% of coastal forests had been displaced due to subsidence and saltwater intrusion, leading to a proliferation of ‘ghost forest’. The consequences for people living along the coast include more tidal flooding, more damaged homes and roads, and more problems with saltwater intruding into farmland and fresh water supplies.

The current drivers that contribute to subsidence include groundwater extraction, and the construction of dams that block the natural flow of sediment that replenishes river deltas, and the drying and compaction of peat soils. However, much of the reason that the mid-Atlantic coastal region is sinking is because the edge of the Laurentide ice sheet, which covered much of northern North America during the height of the most recent Ice Age, ran through northern Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Ice-free lands to the south of that line bulged upwards while ice-covered lands to north were pushed downward by the weight of the ice. When the ice sheet started retreating 12,000 years ago, the mid-Atlantic region began sinking gradually downward, and continues to do so today, while northeastern U.S. and eastern Canada began rising as part of a rebalancing process – isostatic adjustment.

On the other hand, northern Florida has relatively high rates of uplift due to the gradual dissolving and removal of the limestone landscape caused by the infiltration of groundwater.

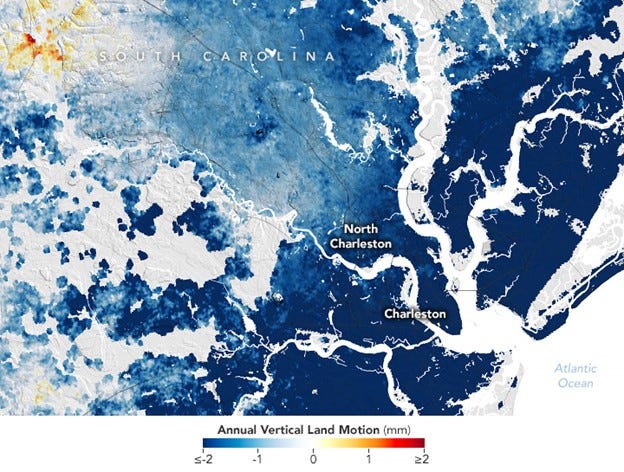

Charleston

The city of Charleston, South Carolina, is at a high risk of coastal flooding, especially when there are storm surges during hurricanes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Land subsidence in Charleston

The city is having to deal with both subsidence and rising seas. With a population of 800,000, it is one of the fastest sinking cities (4mm per year) in the eastern U.S., with some of that thought to be the result of groundwater pumping. Much of the downtown is built on land at a height less than 3m above sea level, and so the frequency of tidal flooding has increased sharply in recent decades. Hence the city is considering building a 11km seawall around the Charleston peninsula to protect its downtown from storm surges.

To download the images: America’s Sinking East Coast (nasa.gov)