[There will be just one post a week for the Christmas period. The next one will consist of links to all the posts in 2024 (for those of you who do not use the app).

My elder son, a civil engineer, has recently been seconded to Britain’s newest railway. So, I thought…. why not submit a post on it?]

Introduction

Building a new railway is an expensive business. Constructing a new route through the English landscape is costing millions of pounds per mile and is taking decades to complete. With the first - and now only - phase currently costed at up to £100 billion by the UK government, Britain’s High Speed 2 (HS2) rail project currently costs £330 million per mile.

By comparison, the $128-billion California High Speed Rail project in the USA comes close to matching HS2’s costs, with some estimates suggesting that it could peak at $200 million per mile. In France, the Tours-Bordeaux TGV line cost around $40 million per mile in the mid-2010s - with much of that line running through sparsely populated agricultural regions. Elsewhere, Chinese companies have driven the Jakarta to Bandung high-speed line through some of Indonesia’s most difficult and densely populated regions for $80 million per mile.

It is clear that population density and topography have a significant effect on construction costs. However, China and Japan have succeeded in threading new high-speed railways through some of the world ‘s most densely populated mega-cities for far less than it will cost Britain to build the 140 miles of track between London and Birmingham.

Why has the project been so expensive?

Several factors have been offered: political interference; chronic short-termism; the UK’s lack of long-term, integrated transport and industrial policies; slow and overly bureaucratic planning and environmental regimes; poor project management; inadequate oversight by civil servants and government.

Since the project was launched in 2012, HS2 has been led by five different CEOs and seven chairmen. It has been overseen by six prime ministers, eight Chancellors and nine transport ministers during a time of political turmoil in the UK.

Others suggest that simple design flaws have been major factors:

· the decision to build the line for 400kph (250 mph) operation - 100 kph faster than the international norm

· a lack of sense over the chosen route, which could have followed existing highway corridors

· the time-consuming process of obtaining permits and conducting environmental studies. In Spain the government obtains all consents, and all environmental permits, and then when they award the contract, the contractor can just focus on delivering the project.

· the relative cost of land and the amount of opposition in many local areas.

‘Northern powerhouses’

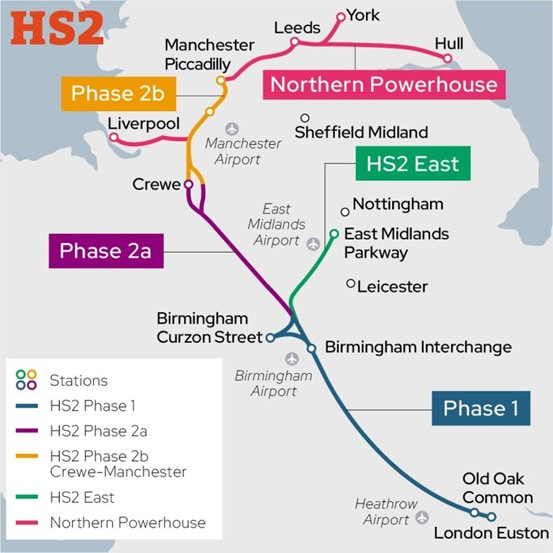

Initially, HS2 seemed to make sense to many (Figure 1). Successive UK governments sold the project to voters as a chance to ‘level up’ deprived post-industrial cities across central and northern regions through investment in improved infrastructure to create ‘northern powerhouses.’

However, right from the start, HS2 generated anger from communities blighted by its construction as well as environmentalists trying to save ancient woodland lying in its path. Also upset were those who argued that even its original price tag was steep for a railway that would offer only marginally faster travel, regardless of whether it would free up capacity on the existing rail network for regional and freight trains.

Figure 1. A plan for HS2 and the Northern Powerhouse (though not the earliest)

Opposition was especially fierce where HS2 cut through the rolling landscapes north of London, dotted with ancient woodlands and historic villages. Wealthy retirees living in the pretty Chiltern Hills found themselves in a surprising coalition with radical environmental campaigners such as Extinction Rebellion as they attempted to halt the project. However, their efforts were in vain and only succeeded in significantly driving up construction costs.

Many miles of extra tunnels and expensive earthworks were added to make the railway hidden from view, adding billions to the price tag but doing almost nothing to reduce opposition from a vociferous anti-HS2 lobby.

For example, in November 2024, it was announced that almost £100 million would be spent on a one-kilometre ‘bat-shed’ covering the track in rural Buckinghamshire to ensure high-speed trains do not disturb bats living in nearby woodland. Its construction was demanded by planning authorities despite a lack of any evidence that bats are affected by passing trains. The Prime Minister, Sir Keir Starmer, described this project as ‘absurd’.

Whereas other countries build their new railways largely at ground level or elevated on seemingly endless concrete viaducts, HS2 chose a far more expensive route that requires 32 miles of tunnels and 130 bridges - including the UK’s longest viaduct. On average, it costs 10 times per mile of track more to build in a tunnel than above ground.

New construction

HS2 will feature some stunning civil engineering achievements when completed. The Colne Valley Viaduct taking the railway out of northwest London stretches for more than two miles over a series of lakes and waterways. Major new stations at London Euston - if it is completed - Old Oak Common, Birmingham Airport and Curzon Street in Birmingham city centre have been planned as modern-day ‘cathedrals’ of transport inspired by Britain’s magnificent Victorian era terminals.

The tracks will be suitable for the fastest regular trains in the world when they eventually start running in the 2030s. Concrete tracks will require much less maintenance than traditional lines. Equipment such as tunnel ventilation shafts will be disguised to blend in with surroundings.

Changes

HS2 was originally conceived as a Y-shaped network that, from Birmingham, would split west and east toward the cities of Manchester and Leeds, connecting the capital with the key city regions across north and central England. (Figure 1)

In November 2021, the eastern arm was cut, followed in 2022 by the Crewe-Manchester section in northwest England and finally a crucial line creating extra capacity between Birmingham and Crewe, the key railway junction for lines to northwest England, Scotland and Wales. This decision has added more than £3 billion to the bill in write-offs and accounting costs for work already undertaken.

At the same time, the then Conservative government stated that the line would not run into central London as planned, instead stopping at a new £1.5 billion transit interchange at Old Oak Common on the western fringes of the city. The Labour government, elected in July 2024, has subsequently stated that they want to invest in infrastructure to stimulate economic growth and complete the tunnels under London to reach the planned terminus at Euston. The final design of Euston is still to be confirmed and there are still doubts about its cost and scope - how many platforms it will have and who will pay for it. The original plan for up to 14 high-speed trains per hour has been scaled back to just eight per hour, with most shuttling only between London and Birmingham.

The future

There are fears that the overall price tag could keep increasing. HS2 supporters maintain that the biggest benefits of the original Y-shaped route would have been generated away from London, in the post-industrial regions of the Midlands and northern England. These areas suffer from poor transport links, leading to low productivity and pockets of deprivation that are among the worst in Europe. Creating fast new rail links between cities such as Nottingham, Sheffield, Leeds and Manchester and freeing up capacity on existing railways for better local services and more freight, promoted hopes that HS2 would initiate much-needed growth outside London.

In the meantime, London continues to dominate the UK economy, sucking investment and widening the already huge gap between the capital and the rest of the country. Services continuing to Manchester, Liverpool and Scotland will have to run at just half the speed of HS2-tracked trains, at most, to reach their destinations. These same high-speed trains, on the non-HS2 tracks, will have to compete for track space with existing inter-city trains, regional services and slow-moving freight on lines that are already struggling to cope with congestion. Many believe that far from increasing capacity for passengers and freight to meet climate change targets, the current plan will lead to reduced rail capacity and higher fares.