Changes in the urban environment in the 2020’s

The impact of the Covid pandemic on urban regeneration

[Here is a modified and updated version of an article I wrote for the UK magazine Geography Review, published in January 2025.]

Introduction

In March 2024, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Jeremy Hunt, announced a £240 million ‘levelling-up’ fund for an area including Canary Wharf in east London – the home of some of the world’s biggest, and richest, banks and offices. Previously, in November 2023, two large investors in the global city-office sector announced significant changes to their financial health. Firstly, Lord Alan Sugar, the star of the BBC reality series The Apprentice, announced that his holding company Amshold, the group through which he holds his London-based property investments, had made a loss of £29 million in the year up to June 2023 (compared to a £15 million pre-tax profit in 2022). Secondly, the co-working city-office space provider WeWork, which has its headquarters in New York, USA, filed for bankruptcy. At its height, WeWork operated in 39 countries, with over 750 work-sharing locations world-wide. The American news network, ABC, described the demise of WeWork as being emblematic of the ‘excesses of business start-up culture’.

What were the reasons for these events, and how symptomatic of the changes to city centre retail and office spaces in the future are they?

Key term: Levelling up: was defined by the UK Conservative government as ‘a moral, social and economic programme for the whole of government.’

The Covid-19 pandemic and city centres

The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on city centres has been profound and multifaceted. While the specific effects vary from city to city, several common trends and consequences can be observed globally:

1. Economically, many businesses in city centres, particularly those in the retail, hospitality and entertainment sectors, experienced significant financial losses. Lockdowns, restrictions on gatherings and the overall decrease in consumer confidence and footfall led to closures and bankruptcies.

2. The pandemic led to the adoption of remote working, leading to a decline in the demand for office spaces in city centres. Subsequently, companies have reconsidered their office needs, with many opting for hybrid or fully remote working. The concept of Working from Home (WFH) became common in towns and cities around the world, which led to a decline in the demand for commercial real estate in urban centres.

3. As the length of the pandemic increased and WFH became more prevalent, more people opted to move away from densely populated city areas to more suburban and rural areas. This in turn led to changes in the demand for city-centre based housing and a consequent increase in suburban-based populations. (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Differences between urban and suburban population growth rates (%)

4. The pandemic accelerated the rise in e-commerce with many traditional retailers facing further challenges as online shopping and contactless services, such as lawyers and accountants, thrived.

5. As WFH increased, demand for public transport in city centres decreased. This also had financial implications for transport providers, even small-scale such as taxi drivers, who saw substantial falls in cash revenues.

6. Culturally, restrictions on social gatherings and events affected cultural activities. The closure of theatres, museums and other venues had both economic and social impacts. Cities dependent on tourism suffered, with consequential negative impacts on hotels, restaurants, and city tour operators.

7. The pandemic highlighted, and in some cases, exacerbated existing social and economic inequalities in city centres. Vulnerable people, including low-income workers and marginalised communities, faced greater challenges during the lockdowns and consequent economic downturns.

The outcome of these effects led to urban planners re-evaluating the design of cities to enhance resilience to future pandemics, and to the long-term consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Declining office use

In July 2023, the US real estate company Cushman & Wakefield announced that office buildings in Manhattan, New York, had a 22% vacancy rate. In London, office vacancy rates were lower, at 9.4% according to real estate services company JLL. However, this rate is almost double the long-term average of 5.5%. In San Francisco, the vacancy rate for offices was 32%, according to the real estate company CBRE. In 2019, the proportion was almost zero there, with startup businesses competing aggressively for office space. In 2022, the San Francisco-based tech company Dropbox announced a loss of £138 million due to unused office space they had planned to sublease.

Elsewhere, some corporations are leaving spaces they have occupied for years; in June 2023, global financial firm HSBC announced it will be leaving its 45-storey headquarters in east London’s Canary Wharf for a much smaller office in the city centre. This is one reason for Jeremy Hunt’s intervention stated in the introduction. Ironically, this forms the backdrop for the opening titles for the BBC tv series The Apprentice mentioned earlier.

Even office buildings that are in use now see more sporadic traffic; they may be bustling on a Wednesday, but by Friday, they are largely empty. Data from global workplace insights company Leesman in 2023 showed three-quarters of UK employees planned to be in the office two or fewer days a week, and mid-week attendance is far higher than Monday or Friday.

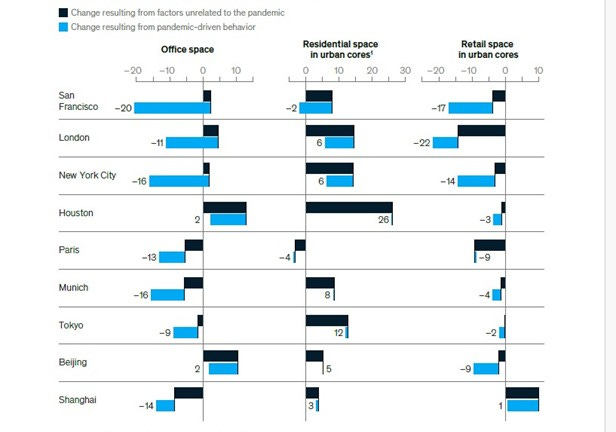

This means many businesses have more space than they are using, with some observers saying it is unlikely companies will need the real estate footprint they had pre-pandemic. The long-term trend is for further declines in the demand for office space (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Changes in expected demand for office, residential and retail space 2019-2030, selected cities (%)

Source: McKinsey

Will companies hold onto these buildings, hoping that workers will come back, or does a new future lie ahead for these once-bustling spaces?

Offices into houses

Some companies are trying to prevent these empty spaces from staying vacant. In some instances, private developers are converting empty buildings into high-end apartment spaces. In Manhattan, New York, developers have raised capital to convert a 1 million square metre office block into a 1300-unit residential tower, at a cost of over $500 million. In Leeds (UK), a seven-storey 1960s office building is being converted into 168 rental apartments. Jeremy Hunt said in his speech that the funding for Canary Wharf and Barking Riverside will ‘build nearly 8,000 houses as well as transforming Canary Wharf into a new hub for life science companies.’

The impact on urban regeneration schemes

The aftermath of the pandemic has highlighted the need for greater flexibility, adaptability, and a re-assessment of priorities when it comes to regeneration. As challenges emerged, the pandemic spurred innovation and prompted a rethinking of how cities are planned and developed in response to evolving societal needs.

Some general aspects of the impact of the pandemic on regeneration schemes are:

· Project delays and disruptions – many regeneration projects faced delays and disruptions due to lockdowns, social distancing, and supply chain disruptions. Some construction sites shut down temporarily.

· Financial challenges – economic uncertainties affected funding for projects; investors became more cautious.

· Re-evaluation of priorities – some cities and developers reconsidered the focus of their schemes with the emerging needs of enhancing public health, creating more green space, and improving future resilience. The relative proportions of residential, commercial, and recreational spaces have been re-examined.

· The rise of WFH – projects saw a shift in demand for flexible workspaces (hot-desking) and a rethinking of the scale and design of office developments.

· The rise of online shopping – the pandemic stoked the existing trend towards online purchases; retail spaces must adapt to become more flexible and digitally orientated.

· Integration of technology into urban planning – including greater digital infrastructure, and the adoption of smart city technologies.

· Community engagement – consultation with local communities and stakeholders has become a crucial aspect of regeneration projects.

National picture

In September 2024, the new Labour Minister for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG), Angela Rayner, published a plan to introduce a system of ‘brownfield passports’ to help speed up development on abandoned urban sites. This followed previous attempts by the Conservative Minister Michael Gove to introduce a law that allowed commercial buildings, including shops and offices, to be turned into homes without planning permission. They failed to become law due to the 2024 general election. The emphasis of the MHCLG initiative is to build housing on previously developed land (brownfield sites), forming part of the new government’s revision of the National Planning Policy Framework. This is linked to its pledge to build 1.5 million homes during its first five years in power.

City example (1) – Sheffield (UK): Furnace Hill and Neepsend

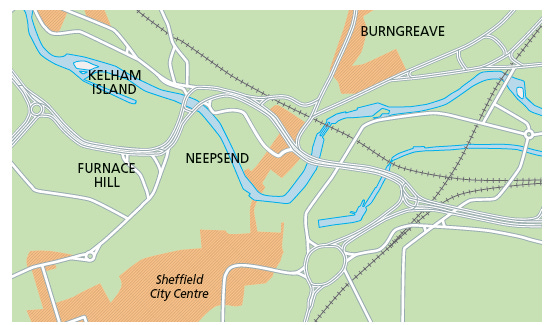

In March 2024, nearly £70 million was awarded by Homes England, the UK government housing agency, to Sheffield City Council for the development of two new neighbourhoods, Furnace Hill and Neepsend, on the north-western edge of the city centre (Figure 3). This regeneration scheme illustrates some of the aspects mentioned above.

Figure 3

The development will take place on existing brownfield land and ‘transform existing developments creating commercial space, local facilities, 1,300 homes and public green space’. The Council Leader, Tom Hunt, said a minimum of 20% of the new homes would be ‘truly affordable accommodation’ which would be ‘within the reach of everyone’.

In the plans, Furnace Hill will become a liveable neighbourhood with ‘a focus on people and leisure space’. The former industrial heritage of the area will also be ‘celebrated by creating a new public realm with the iconic Cementation Furnace at its core’. (Figure 4)

The Council said the new neighbourhood at Neepsend would ‘promote the best of city life’ with ‘added benefits of waterside living alongside the River Don’. The plans for Neepsend sought to attract local families to the centre of the city, by providing a range of housing, amenities, and green public spaces. The developments will also include a network of public spaces and streets to improve connectivity between the city centre and Kelham Island (an industrial museum on the banks of the River Don).

Figure 4. The new community at Furnace Hill would be built on brownfield land near Cementation Furnace

City example (2) – Liverpool (UK): a new Central Park

A new major public park will be created in Liverpool as part of a £55m government investment for the city. Homes England will invest a large amount of money into a major housing scheme at the Central Docks, the largest neighbourhood within Liverpool Waters - the city's largest brownfield site. The plans will see around 2,350 new homes created. It will also include the creation of a huge new public park.

Full planning permission has already been granted, with plans for the Central Docks area including the creation of an interconnected network of public spaces. The proposed new landscape will also involve the planting of hundreds of trees, with a centrepiece of ‘Central Park’ a sprawling 2.1-hectare area set to become one of the city’s largest urban green spaces.

The Park’s design will celebrate the site's industrial heritage and coastal location, blending coastal and woodland plantations, wetlands, community gardens, and open parkland. The park will feature amenities such as shelters, recreational facilities, and wildlife habitats, to be enjoyed by both residents and visitors. It is hoped that the scheme will transform the historic disused dockland into a spectacular new neighbourhood in keeping with the iconic waterfront.

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic has forced town centres and associated office developments into a period of transition. It has been a transition involving the loss of many well-known retailers (such as Wilko in the UK), a reduction in the use of office space and a loss of financial return for many city investors. It has forced the town centre economy to become more diverse in terms of the type of retailers, a mix of uses and a range of activities to make the transition more positive. Many hope that it might deliver us from the clone towns of the early 2000s and create town centres nearer to those that exist in the popular imagination – community hubs with a range of distinctive retailers and leisure uses with a strong local identity and a sense of place.

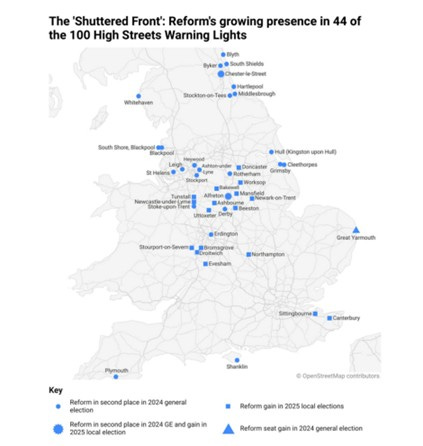

Postscript - a political point: The rise of the ‘new’ political party, Reform, in the UK has been linked to the declining state of the British ‘high street’. Some commentators have stated that a declining High Street is symptomatic of a deeper malaise and unhappiness in the societies in many UK towns and cities, which the Reform Party has sought to exploit in recent elections (see map below).

[For subscribers outside the UK, the Reform Party has links and similarities to the MAGA Republican Party in the USA.]

Very useful topic.

Check out my Urban Articles

https://ritchiecunninghams.substack.com/t/urban-geography