China’s Belt and Road Project – an evaluation

‘Every time China visits, we get a hospital; every time Britain visits, we get a lecture’. Unnamed Kenyan government official

Introduction

China has announced plans to expand its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) on the 10th anniversary of its inception. In 2013, China sought to expand its international reach which led to the development of ports, railways, power plants and roads by Chinese companies across the developing and emerging world – South Asia, South-east Asia, and Africa. The ‘Belt’ signified the land routes and the ‘Road’ signified those across water. (Figure 1)

Figure 1

The BRI was one of Xi Jinping’s earliest signature projects. A clear aim was for the Chinese government invest in infrastructure projects throughout the world, giving a boost to those countries’ economies while increasing China’s trade opportunities - a massive win-win. There was also the notion that such a financial outlay would win China geopolitical friends and allies around the world (as illustrated by the quote above) while also enhancing its access to critical natural resources and potentially military bases. It is reported that China has already spent $1 trillion on the Belt and Road.

How does it operate?

However, the common view that China would pay for infrastructure in many countries around the world with its own money, and that money would be regained from the revenues from economic growth in those countries has proved to be incorrect. Instead, what China did was loan countries money to build infrastructure projects. China’s government would then help plan those projects. The borrowing country would use the money it borrowed from China to build the infrastructure, often bringing in and paying Chinese contractors to do the work.

From China’s perspective, setting aside the security and diplomatic benefits, this looked like a good arrangement. Their contractors received massive amounts of revenue, and then the Chinese government got its money back when the recipient country paid back the loan. Furthermore, the infrastructure being built acted as collateral, so if the recipient country couldn’t pay China back, at least it would own a piece of infrastructure in a foreign country.

From the receiving country’s point of view, it was a lot riskier. If the infrastructure project doesn’t raise enough money to pay back the loans, the government would have to pay China back using tax money; derived from its citizens. If it can’t do that, it has to surrender the collateral - i.e. the infrastructure - and endure a default that will impair its ability to borrow internationally and will cause a deep economic recession.

Has the policy been effective?

The BRI recipient countries also made a big assumption that China would design some useful and effective infrastructure projects. However, in several cases, China has not done that. Many of the projects were poorly planned and executed:

· In Myanmar, Chinese planners assumed that they could move peasants off their land to build some pipelines as per standard practice in China; instead, there have been protests.

· In Sri Lanka, China built a new port at Hambantota that was supposed to boost Sri Lanka’s trade. However, most shippers kept trading at the capital city of Colombo, which had recently improved its port infrastructure. Hambantota has become a huge white elephant, which hasn’t generated enough cash to pay back the loans that Sri Lanka took from China to build it. So, it defaulted, and China now owns and controls the port.

· In Ecuador, thousands of cracks have emerged in the $2.7 billion Coca Codo Sinclair HEP plant, raising concerns that Ecuador’s biggest source of power could break down.

· In Pakistan, officials have shut down the Neelum-Jhelum HEP plant after detecting cracks in a tunnel.

· Uganda’s power generation company said it has identified more than 500 defects in a Chinese-built 183MW HEP plant on the River Nile that has suffered frequent breakdowns. Completion of another Chinese-built HEP plant further down the Nile is three years behind schedule, also blamed on various construction defects, including cracked walls.

· In Angola, in a vast social housing project outside the capital of Luanda, locals are complaining about cracked walls, mouldy ceilings and poor construction.

· Indonesia’s high-speed rail line in Jakarta, sometimes touted as the most successful Belt and Road project, has had a massive cost overrun and has fallen years behind schedule – it is only 88 miles long. [Author’s note – sounds familiar??]

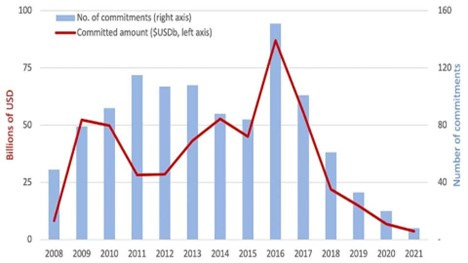

It is little surprise that the amount of money being invested in the Initiative is falling (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The falling amount of money invested in the Belt and Road Initiative

Source: Boston University via China Global South Project

Debt

Borrowing countries are now saddled with a lot of debt. China has forgiven some of it, but in other cases it is choosing to be intransigent. For example, in Sri Lanka, which is in the middle of a severe economic crisis, China is refusing to cooperate with other international lenders on a rescue package.

According to The Economist:

‘The IMF cannot lend more unless Sri Lanka restructures its debts, since the country owes so much elsewhere that officials cannot otherwise be sure they will get their money back. Therefore, by refusing to take a haircut on its debts, China is holding up Sri Lanka’s restructuring - as it is in other indebted countries, too.’

Many countries are indebted to China, including Pakistan, Kenya, Zambia, Laos, and Mongolia. These are finding that paying back debt is consuming an ever-greater amount of the tax revenue needed to keep schools open, provide electricity and pay for food and fuel. It is reported that for some countries as much as 50% of foreign loans are from China and most were devoting more than a third of government revenue to paying off such debt.

This is damaging China’s image in the world. Many countries of the Global South saw China in a highly positive light (as in the opening quote). Before the Initiative, they saw that money from the West often came with strings attached. China would be different.

Conclusion

Some economists now believe that the BRI has failed, and the cash tap is being shut off. President Biden has called it a ‘debt and noose’ agreement. Indeed, China’s largesse may be replaced by resentment and distrust. For its part, China doesn’t appear to be wanting greater geopolitical influence; instead, it appears to simply be walking away with as much of the original money as it can and leaving developing countries feeling bitter. Throughout the creation of the BRI, it has been suggested China’s government treated countries such as Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Zambia as if they were Chinese provinces - assuming they could strongarm their populations into supporting new infrastructure, prioritizing visible growth over efficiency and profitability, and counting on those countries to just accept the outcomes, even when they haven’t been as successful as hoped.

Back at home, after a decade in power, President Xi now confronts a slowing Chinese economy, a looming crisis in the housing market, spiralling youth unemployment, not to mention a demographic ageing time bomb.