Contrasting perspectives on population and resources

The wager between Ehrlich and Simon; and yes, Malthus and Boserup

[You may have seen the catastrophic storm that affected the western coast of Alaska last weekend – caused by the remnants of typhoon Halong. You can find an account of the event here.

The excellent Substack of (Sky journalist) Ed Conway is worth reading if you study Resource security. His latest post on rare earths is also useful for Global systems. You can find it here.

Finally, there was some very disappointing news in the UK educational publishing world yesterday – applicable to a whole range of academic subjects. I will say more when I can, but rest assured, this free Substack is staying around. Feel free to spread the word.]

Various theories have been put forward to explain the relationship between population and resources, which is seen by some as difficult to keep in balance. The theories are often categorised as being either pessimistic or optimistic.

Most A Level students will be aware of the theories of Malthus and Boserup – for the three who don’t, I will add my summary of their theories at the end of this piece, before the final section. But first, the battle of ideas between Ehrlich and Simon.

The wager between Julian Simon and Paul Ehrlich

In 1980 the biologist Paul Ehrlich agreed to a wager with the economist Julian Simon on how the prices of five raw materials would change over the following decade. Paul Ehrlich had a clear Malthusian expectation. He thought population growth would quickly deplete the planet’s resources. Consequently, he expected that the cost of resources - including minerals - would rise steeply as they became more scarce.

Conversely, the optimistic social scientist Julian Simon expected the opposite. Simon thought that human innovation and ingenuity would overcome resource shortages, and the price of resources would not rise but instead fall. In the magazine Social Science Quarterly he challenged Ehrlich to put money on his bet.

Simon offered Ehrlich the chance to choose any resource he wanted. Ehrlich chose five: chromium, copper, nickel, tin, and tungsten. The two bet $1,000 - $200 on each metal - on whether inflation-adjusted prices of these resources in September 1990 would be higher or lower than they were in September 1980. If prices had increased, Ehrlich would win. If they had fallen, victory would go to Simon.

So, what was the outcome? By 1990, the $1000 ‘basket’ of metals (at 1980 prices) had fallen in value. Taking in adjustments for inflation, the reduction in prices was $576 – quite a substantial reduction. [It is worth stating that the value of all the metals did fall but not in equal proportions, some (tin and tungsten) fell more than others]. None had increased in price. So, Simon won the bet.

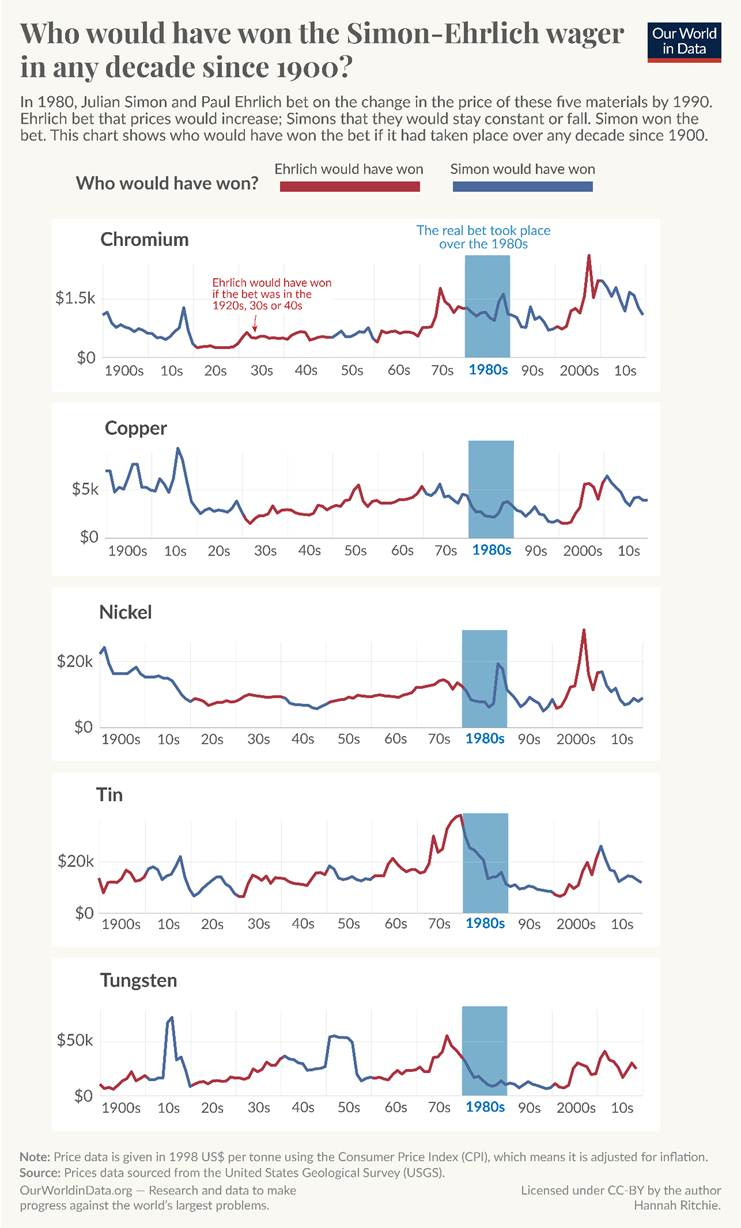

The data scientist, Hannah Ritchie, in her work at Our World in Data, has taken this story a little further. She has looked at how the prices (again inflation-adjusted) of these five metals would have played into the wager in other decades, both before 1980 and after 1990. The outcomes of this exercise are shown in Figure 1 below.

The price of all five elements varied over time. For example, the price of chromium in some decades fell. In others, it went up. Whenever the price was higher at the end of the decade than at the beginning, Ehrlich would have won - those segments coloured red. Simon would have won when the price fell between the beginning and the end of a decade - the segments coloured blue.

Figure 1. Who would have won the Simon-Ehrlich wager in each decade since 1900?

Ritchie has argued that a significant issue is that Simon and Ehrlich agreed to a bet over short-term changes. Their decade-long wager was vulnerable to short-term fluctuations, which often had nothing to do with actual changes in physical supply and demand. Instead, they were influenced by geopolitical or temporary economic forces. That means either could have won depending on random year-to-year fluctuations that did not reflect their worldview.

She states that a more meaningful test for their arguments is the change in prices in the long run. Looking at Figure 3, over the period of 120 years, (adjusted) prices did not change dramatically. The (adjusted) prices of the five metals are not much different from what they were in 1900. Chromium is, perhaps, the one exception where average prices in the last few decades have been higher than they were in the early 20th century (although prices in 2020 were the same as they were in 1900).

Overall, material values have fluctuated up and down but around a reasonably consistent level. Furthermore, this is even though the world produces much more of these materials. Today, the world produces 40 times as much copper annually and 250 times as much nickel as it did in 1900.

The fact that we produce far more materials than we did in the past, yet prices have barely changed, suggests that contrary to Ehrlich’s prediction, we are not close to running out of these materials any time soon. Simon’s worldview seems to be the right one.

The ‘classic’ case for pessimism: Thomas Malthus

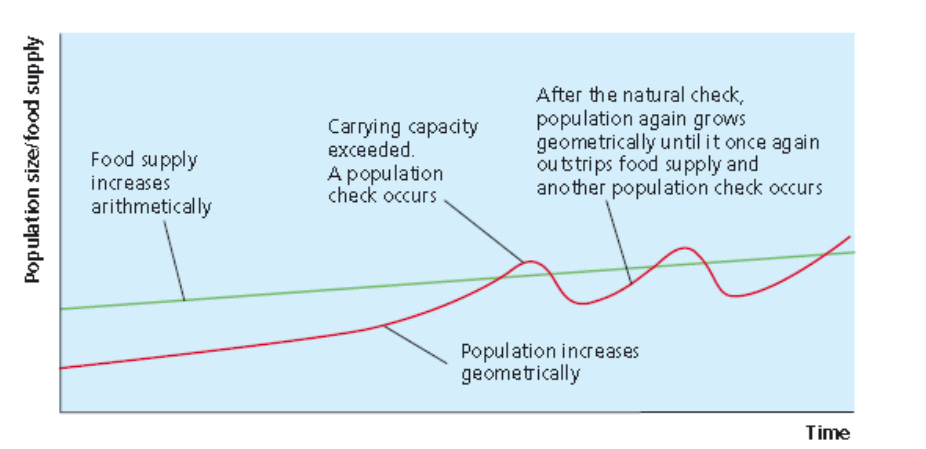

Thomas Malthus pointed out in his work ‘An essay on the Principle of Population’ in 1798 that population growth was geometric (1, 2, 4, 8, 16 etc.) while food supply could only grow arithmetically (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). This, inevitably, leads to a point where carrying capacity is exceeded, leading to a food shortage [Figure 2].

Figure 2. Malthus’ theory

Malthus believed that increasing the food supply dramatically was not possible, and so food shortages would lead to a series of population checks which would reduce the population size. These checks would either increase the death rate (a ‘positive check’) or reduce the birth rate (a ‘preventative check’). Examples of positive checks include war, famine and epidemic. Malthus noted that these tend to be suffered disproportionately by the poor. Preventative checks occur when individuals realise that there may not be enough food to support a family, and so they opt for later marriages or sexual abstinence (note this was before the days of artificial contraception). Malthus believed a series of cycles would occur, in which carrying capacity was exceeded, each leading to a period of population check. The assumption that sexual relations are a fundamental part of human nature led Malthus to argue pessimistically that preventative checks would never reduce the population sufficiently and that we would never escape from cruel positive checks. In other words, starvation, war and disease are inevitable.

The ‘classic’ case for optimism: Ester Boserup

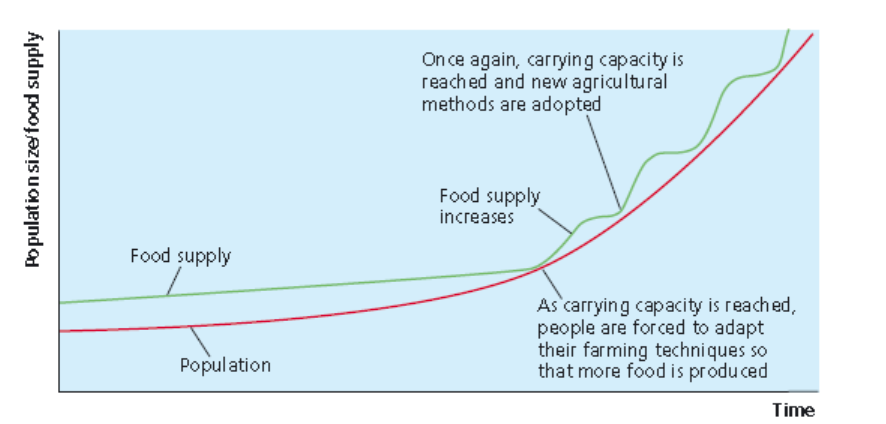

Ester Boserup, a UN agricultural economist, argued in 1965 that, while Malthus believed that the amount of food supply determined population size, it was the size of the population that determined the level of food supply. By examining the development of agriculture in a number of regions, Boserup concluded that as population size reached carrying capacity, societies were forced to make radical agricultural changes to ensure there was enough food [Figure 3]. For example, Boserup noted that the people of Java in Indonesia had over time adapted their farming practices several times to feed a larger population. They had moved from long fallow farming (land is farmed for 1–3 years and then left to recover for 10–20 years) to short fallow, and then to annual cropping (a crop is harvested annually from a piece of land) to multiple cropping (a piece of land produces more than one annual crop). Such optimists, therefore, do not regard population size as a problem, because humans can invent solutions to any food shortages. They argue that agricultural advances over the last century, such as the Green Revolution, and more recently, the development of genetically modified foods, show this. In essence, ‘necessity is the mother of invention’.

Figure 3. Boserup’s view

And finally …

The debate regarding the balance between population and resources was re-ignited in 2013 when two books with almost identical titles were published. In 10 Billion, Stephen Emmott argued that our rapidly growing global population is becoming increasingly unsustainable. Our only solution is to radically reduce our consumption levels. However, he pessimistically believes that we won’t manage this and that we are ‘doomed’.

Danny Dorling on the other hand is more optimistic in his book Population 10 Billion. He suggests that we need to dismiss the concept of carrying capacity and focus instead on imagining how ten billion of us can all live well on planet Earth.

The pessimist v. optimist debate is likely to continue.