Demography and Place (Japan)

Why is there a housing crisis in Japan when its population is tumbling?

Japan is facing a demographic crisis with its population falling rapidly. Yet, demand for new houses is increasing greatly too. These two trends may initially seem incongruous, with a falling population seemingly offsetting the need for new housing. However, the relationship between population and housing is complex, involving elements of Place, both economic and cultural.

Japan’s population

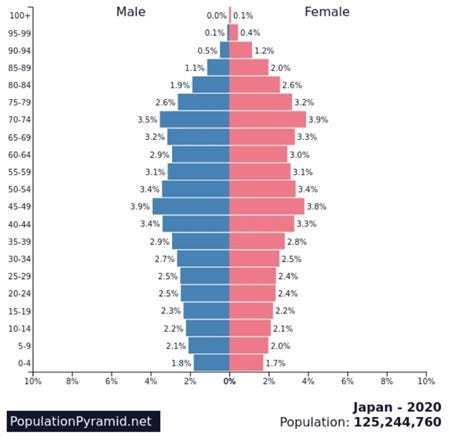

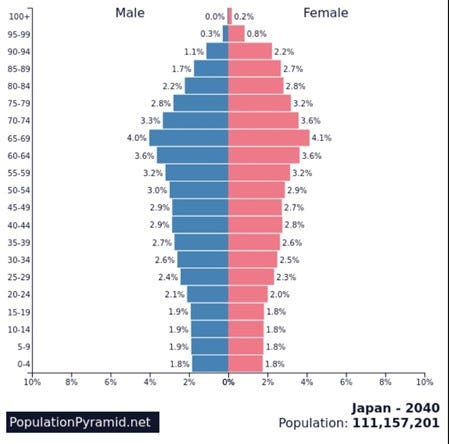

Japan has the world’s oldest population, measured by the proportion of people aged 65 and over. National data for 2020 showed that 29% of the total population of the country (125 million) was aged 65 and over, with more than 10% aged 80 and over. The proportion of 65 and over is expected to reach 35% by 2040. Japan also has one of the lowest birth rates in the world, with fewer than 1 million babies born in 2022, the lowest since records began. Its total population is projected to fall significantly in the coming century (Figures 1a and b, Table 1 and Figure 2).

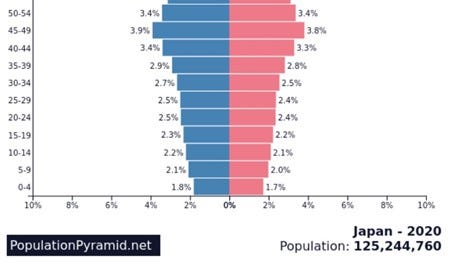

Figure 1a. Japan population pyramid 2020

Figure 1b Japan population pyramid 2040 (projected)

Figure 2. A shrinking population (naturally)

In January 2023, the Japanese Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida, said the country was ‘on the brink of not being able function as a society’ because of the combination of an elderly population and its declining birth rate. Many elderly people continue to work – workers of 65 and over make up 13% of the national workforce. However, this has done little to relieve the burden on the country’s pension and health care systems. It should also be noted that the Government (and the population generally) is hesitant about accepting migrant workers as a solution to falling fertility and lower numbers of working-age people (see below).

Demographic collapse

About 1.2 million people were born each year in Japan in the mid-1990s, when the country was entering a long phase of economic stagnation after decades of rapid growth. However, in 2022, fewer than 800,000 babies were delivered, with a much faster declining curve than expected. The Japanese government projects that, if this trend is not reversed, the country’s current 125 million inhabitants will drop to 100 million around 2050. The population is expected to fall even lower - to 60 million - by the end of the century. The demographic downward curve is so steep that it threatens the strength of the country’s economic future. There are questions about Japan’s ability to sustain the burden of pensions and care for the elderly, or to have a healthy workforce made up of young people with sufficient innovative industrial capacity to grow the economy. Furthermore, some 500 schools are closing every year.

Japan is a country with very traditional conservative values when it comes to aspects of population and society. Gender equality in the workplace is increasing in importance, but not as rapidly as many other western countries. The country does not have many immigrants, with little desire to increase their numbers.

Millions of empty houses

The National Statistics Agency of Japan (NSA) has reported that there more than 8 million empty houses across the country. The true number is probably greater. For example, Akita Prefecture is in the north-western part of Honshu Island. In 2018, according to NSA there were almost 61,000 empty houses here, representing 14% of all houses in the area. Some are in a bad condition; most are in rural areas.

What are the reasons for this phenomenon?

1. Financial: in Japan tax relief is available for land upon which a house stands, which may be as much as one sixth of the value. If the house is removed so is tax relief, which means that more tax must be paid to the government. In simple terms, keeping a house, even an empty one, reduces tax on that land.

2. Spiritual: many people have a close association with houses that have been in families for generations, some over centuries. People do not want memories torn down with the house. In addition, many families keep their holdings and heirlooms in their ‘ancestral home’.

3. Economic: in remote and rural areas, the economy depends on traditional industries such as farming of rice and brewing sake. Educational opportunities are not as great, especially higher education, and as a result many young people move to cities such as Tokyo, Sendai, and Osaka.

4. Emigration: just over 500,000 Japanese live permanently abroad: 0.4% of the resident population. Another 700,000 went abroad in 2022, for long-term stays of more than three months. The number of Japanese emigrating is growing, and it is the younger people who leave.

5. Ageing: older generations move away from rural areas for better medical care, or to be near relatives who can look after them.

Cultural factors

Traditionally, it was common to have three generations living in one house – typically older parents lived with the eldest son and his family, which helped share household resources and finances. This also made succession easier including passing on ownership of the house.

But this changed after World War 2. Many young people moved to the cities for employment and established their own household there. So generational housing drifted into disrepair. Today’s older generations now have more money, and their own social security including pensions. Hence, families have split up.

Consequently, the traditional family arrangement has begun to decline, and household sizes are getting smaller. In 1970, almost 50% of households were married couples with children, and 14% were three-generational. Today, smaller households with just one or two people have expanded. Marriage rates have fallen too - single person households are also now the most common, 38%. So, when they die, another empty property will be created.

Other factors

Life expectancy is over 80 for both men and women, due to advanced healthcare, social security systems, technology, and education (Table 1). The current fertility rate is only 1.3, well below 2.1, the replacement level. Falling marriage rates are a major reason for the falling reproductive rate. Children out of wedlock in Japan are very rare – again a feature of traditional cultural factors.

Economic factors also play a role here. Even in a prosperous society like Japan’s, there is an economic brake to child-rearing. Public education is free only until children reach the age of 15 but many families want private education for their children, and that is expensive. Free nursery provision is not universal. Prime Minister Kishida has recognized that action must be taken to change this situation. In June 2023, he announced his intention to double public spending on childcare. The participation rate of women in the labour market has increased, from 60% at the beginning of the 2000s to 74% today. This growing figure is of enormous importance in a country with a shortage of workers.

Immigration

There are 2.7 million foreign-born people living in Japan. This represents just over 2% of the total population - a small number when compared to the figures of other advanced democracies. The Japanese government has tried to make regulations more flexible in recent years to attract foreign labour, but little progress has been made. In fact, during the Covid pandemic, the number of foreigners dropped. Japan’s language and strong cultural roots appear to inhibit the attraction and full integration of foreigners.

Issues arising from the empty houses.

In rural areas, the neglected properties can attract wild animals, such as bears. In winter, when heavy snow comes, traditional unmaintained wooden houses can be in danger of collapse. Even damaged buildings cannot be removed without the permission of the house owners.

Challenges are presented by people moving away, often not leaving a forwarding address. In some parts of the country, relocation schemes have seen vacant homes repaired and repurposed as cafes, farm shops, craft workshops and tourist accommodation. But in general, there are simply too many empty properties.

Contemporary issues

People now prefer modern houses to the more traditional wooden ones. However, many new houses in Japan lose value rapidly - even over a period as short as 30 years. [Note this is a different situation to many other countries]

There are several reasons for this economic trend. Japan is prone to tectonic hazards, and as a result new building codes are introduced regularly. Energy efficiency rules also change frequently. Updates to both can be as often as every 10 years. Consequently, houses, even those recently built, are not compliant with the ever-changing rules. Owners tend not to spend to update, so the value of their houses decreases.

On the other hand, newer houses with the updates increase in price. Furthermore, following cultural trends, building companies target their construction at the demand – targeting small families and single people. Consequently, more than 800,000 new houses are built each year, despite the large numbers of empty ones.

The government operates a dual policy that gives support to builders and new buyers and gives financial incentives to occupy the older houses. It is keen to boost the economy with house building yet is also keen to get people to renovate the older ones.

Conclusion

Japan is experiencing an unusual set of issues: its population is falling; house availability is increasing; demand for new houses is increasing; and houses (and empty plots of land) are losing value. What could be done to address these?

The government could change the tax coding of properties. Currently, property taxes favour land with structures on it, and inheritance taxes are also low. These exemptions could be removed as they would encourage the demolition of older properties and the better use of land. Following the prevalence of ‘Working from Home’ during the Covid pandemic, more service jobs could be moved to rural areas. Younger people could stay or move there, and yet could still work for firms in the big cities, working in properties in the countryside. Some ‘start-up’ companies have already moved to abandoned large old houses using them for their offices.

Extra

You can listen to a 25-minute BBC podcast on the issue here.

And a postscript: China’s population shrinks again

Despite an increase in births in 2024, the population of the People's Republic of China saw its third consecutive year of population decline. The number of births in 2024 reached 9.54 million, up from 9.02 million in 2023. However, this was not enough to offset the 10.93 million deaths. China's population fell from 1.409 billion to 1.408 billion.

China's authorities are taking measures to encourage marriage and childbearing, but China is just one of several countries representing a worldwide trend of dropping fertility rates, with its East Asian neighbours Japan and South Korea also leading the world in declining population and the elderly becoming a larger and larger proportion of the population.