The ongoing El Niño event in 2023 is disrupting rainfall patterns across the planet, with mixed consequences for food production. Too much rain in some places, and too little in others, is projected to affect crop yields and leave 110 million people in need of food assistance, according to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET).

El Niño is a natural climate phenomenon characterised by warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. This cyclical warming disrupts atmospheric circulation in ways that shift rainfall patterns. Wetter conditions are expected in the southern United States and the Horn of Africa and drier conditions are likely over southern Africa, Latin America, Australia, and parts of southeastern Asia.

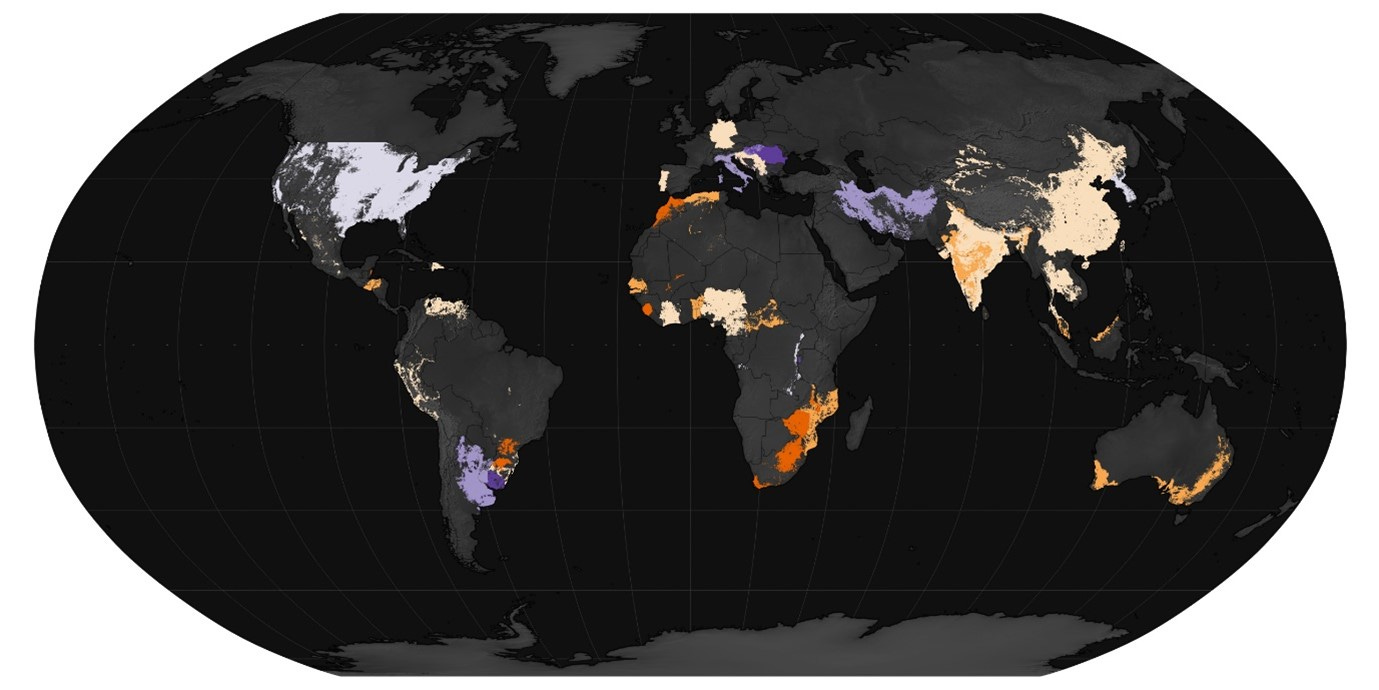

Figure 1. El Niño global food impacts: Towards orange - negative; towards purple - positive.

This year’s El Niño event, is expected to contribute to high levels of food insecurity in certain regions. Figure 1, developed by FEWS NET, shows the projected impact of El Niño on key commodity crops, including wheat, maize (corn), rice, soybean, and sorghum. The map was based on an analysis of historical crop yields and climate data from 1961 to 2020.

El Niño is likely to bring poor maize yields in southern Africa and Central America due to drought. Wheat yields in Australia and rice yields in Southeast Asia are also reduced. On the other hand, on average, global soybean yields improve during an El Niño event. Meanwhile, above-average rainfall is expected to facilitate the gradual recovery from 3-year long droughts in much of the Horn of Africa and Afghanistan.

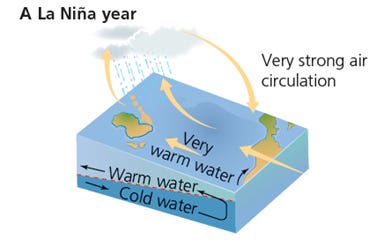

What follows is a series of bullet points that explain each of a ‘normal’ year, an El Niño year, and a La Niña year, together with explanatory diagrams.

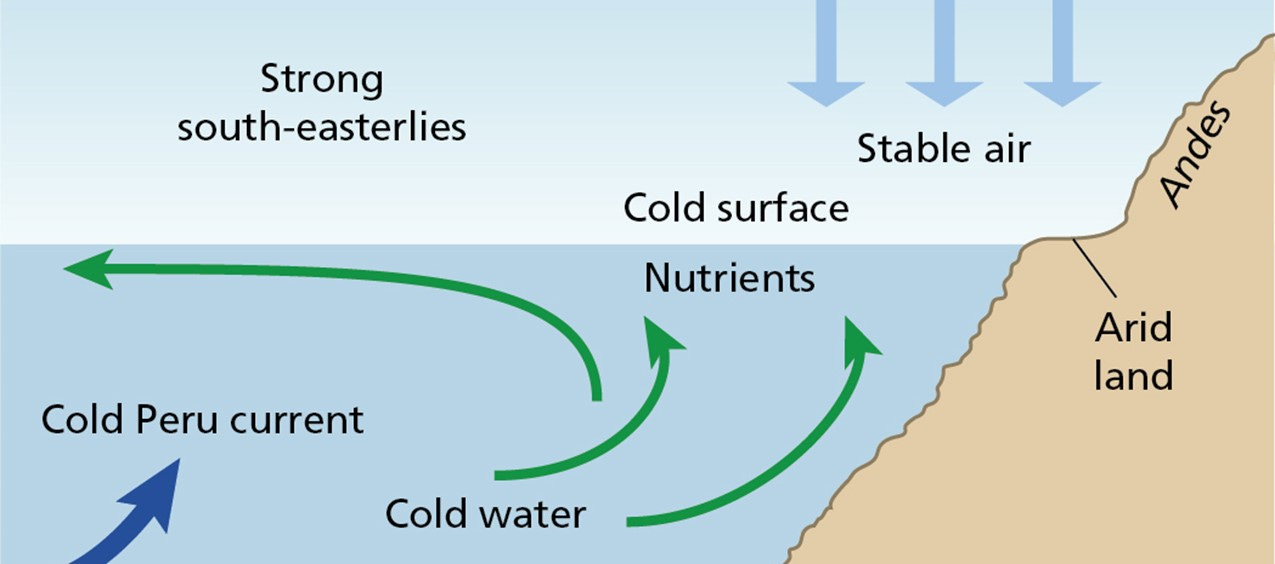

A normal year

Normal conditions are:

• high pressure exists in the eastern Pacific, low pressure in the western Pacific

• surface trade winds blow east to west across the Pacific Ocean, with compensatory upper atmosphere westerly winds (the Walker Circulation)

• these push warm water across the sea surface from east to west

• upwelling of cold water takes place off the west coast of Peru, together with more cold water supplied by the cold Peruvian ocean current

• dry weather exists in coastal Peru, with rain in northern Australia.

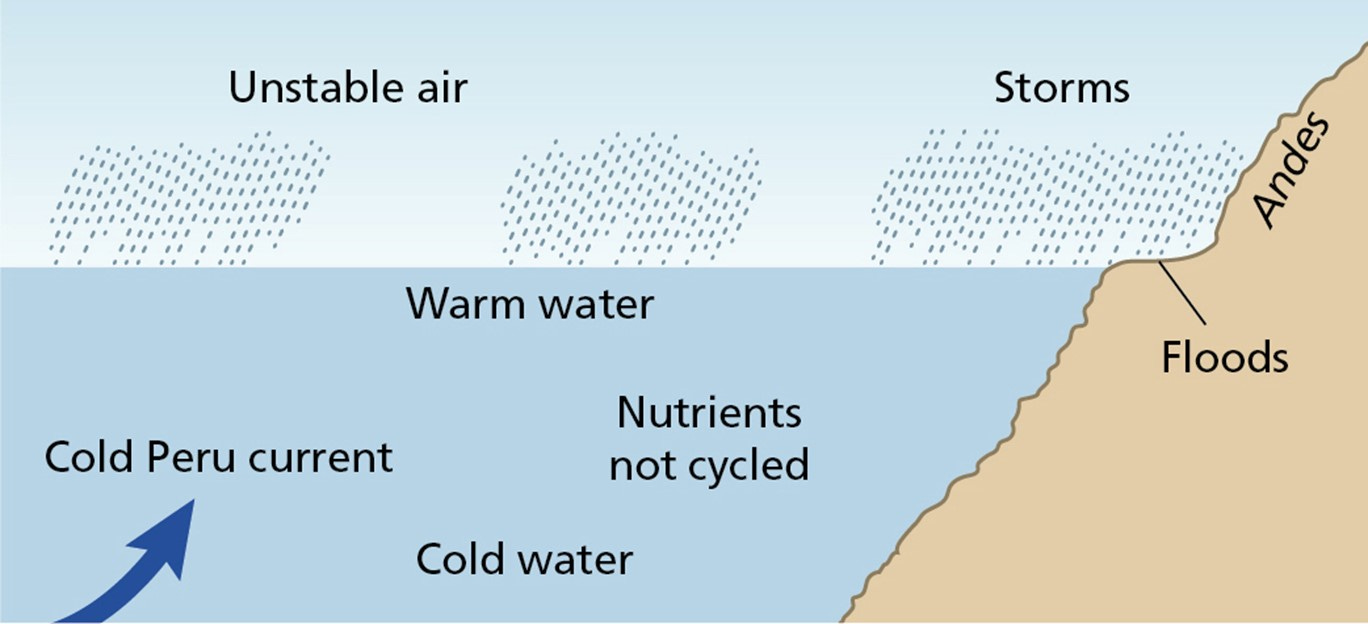

An El Niño year

In an El Niño year:

• the trade winds become weaker, and may even reverse

• low pressure develops over the eastern Pacific, with high pressure to the west

• warm water replaces cold water off the coast of Peru

• waters off the coast of northern Australia become cooler

• rainfall totals in northern Australia and Indonesia reduce, and the dry conditions often spread to India and southeast Asia

• rain falls in northwestern South America

El Nino impacts

In South America, there are a variety of impacts:

• an increased possibility of flooding on the western coast of northern South America

• drier conditions east of the Andes, in Amazonia

• wetter conditions in southern Brazil and northern Argentina

In Australia and the western Pacific basin:

• weaker monsoons across much of Asia

• reduction in number and intensity of tropical storms

• an increase in wildfires with the drier conditions

A La Niña year

La Niña events act independently – they are not associated with El Nino events:

• they involve the build-up of cooler-than-usual subsurface water in the eastern Pacific Ocean

• very warm waters build up in the western Pacific

• they create severe drought conditions in the eastern Pacific coastlands/western and southern South America

• very wet weather can be experienced in northern Australia and Indonesia

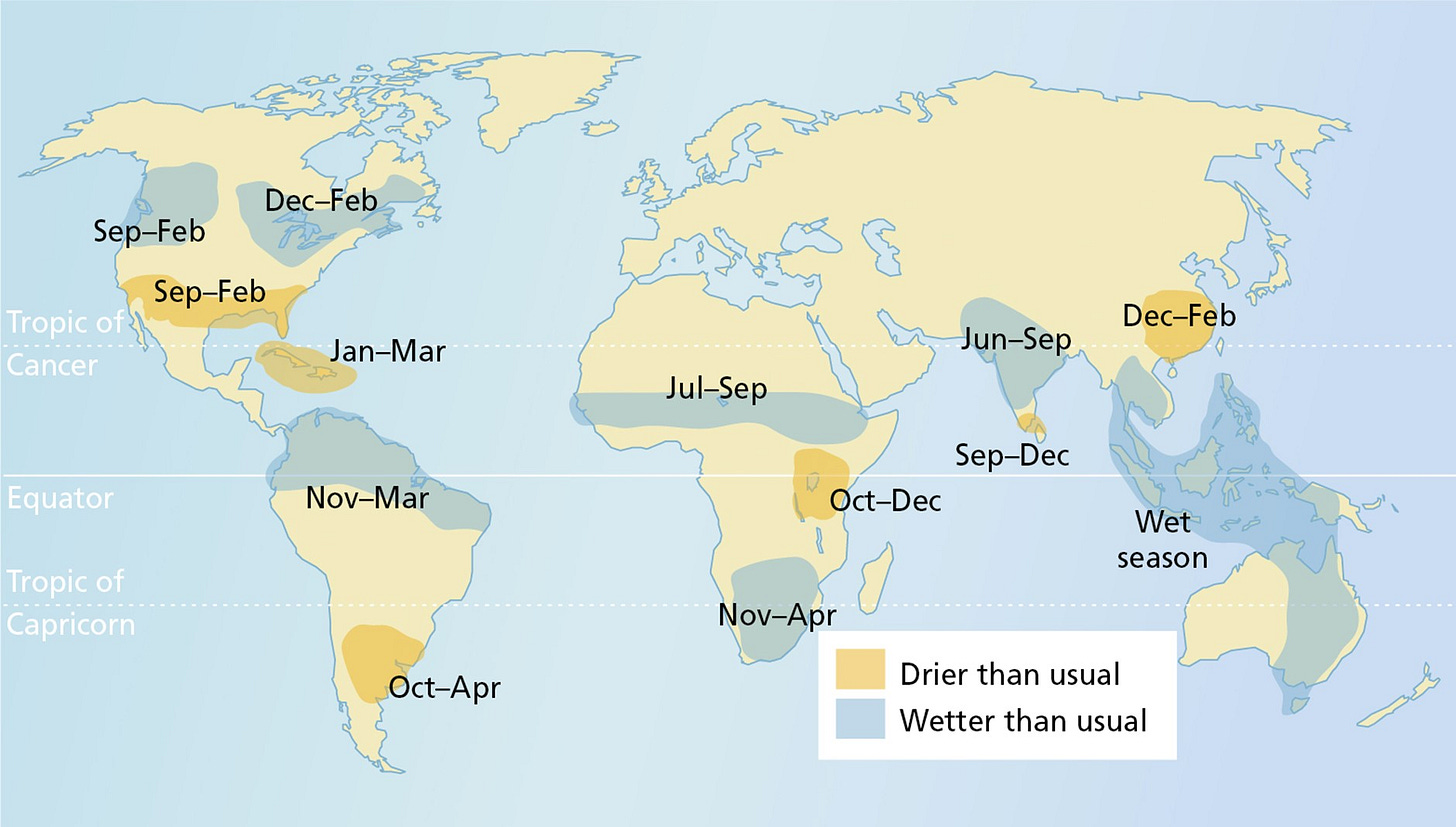

Figure 2. Global changes to rainfall and drought in a La Niña year

La Niña impacts

A variety of global phenomena have been linked to La Niña events:

• flooding in Queensland, Australia in 2010/11 – more than 80 people were killed

• heavy snowstorms in northern USA/southern Canada in 2010

• strong tornadoes in the southern USA in 2011

• increases in transmissible diseases in wetter areas, e.g. malaria in southeast Asia and Australian encephalitis (also known as Murray Valley encephalitis) in southeast Australia.

Managing El Niño and La Niña impacts

Managing the impacts of these global events is difficult because:

• they cannot be predicted with accuracy

• they affect large parts of the globe, not just the Pacific

• some of the countries affected do not have the resources to cope

• there are indirect impacts on other parts of the world though trade and aid

However, increasing awareness and research should make it possible to anticipate the impacts and enable decision-making to reduce any negative impacts or take advantage of positive impacts.