Hazard and place

Examining the synoptic links that exist between hazardous events and the places they affect.

Introduction

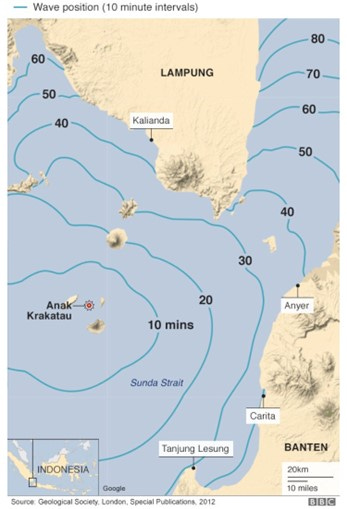

The devastating tectonic events that took place in Indonesia towards the end of 2018 highlighted the connections between hazardous events and the places they affect. They involved a tsunami caused by an earthquake that affected the town of Palu on the island of Sulawesi, and another tsunami caused by the partial collapse of the volcano on Anak Krakatau destroying the beach resort of Tanjung Lesung. For the former, it was the combination of a nearby earthquake, a funnel-shaped bay and a local festival taking place on the beach that led to the 2000+ deaths. For the latter, it was the proximity of the volcano (only 30 minutes wave time away [Figure 1]) combined with tourist-related activities and infrastructure that proved lethal. They both had disastrous outcomes for the people of their areas – reinforcing the view that a natural hazard event only becomes a disaster when it affects people and places.

Figure 1. Wave times based on collapse of SW flank of Anak Krakatau volcano

The Population and Release (PAR) model

The PAR model (Figure 2) shows how the characteristics of a hazard and a place connect to create a disaster. In simple terms it describes where PLACE and HAZARD collide.

Figure 2. The PAR model

Risk: The probability of a hazard occurring and creating a loss of lives and/or livelihoods

Vulnerability: The risk of exposure to hazards combined with an inability to cope with them.

The model shows that:

• the socio-economic context of the place is important. The political systems (governance), income levels, economic strength, levels of education and training, rates of population change and levels of investment in a place all impact on its degree of vulnerability

• the nature of the hazard is also key, whether a volcano, earthquake, storm or landslide

• both the context and the hazard place pressure on the place affected

• the release of that pressure comes with a reduction in the vulnerability of the place affected, which in turn often depends on the quality of governance in the place.

Inequality and governance

Resilience: The degree to which a population or environment can absorb a hazardous event and yet remain within the same state of organisation, i.e. its ability to cope with stress and recover.

Inequality is also a key factor. It influences access to education and training, housing and healthcare and so influences a place’s vulnerability and resilience. The Human Development Index (HDI) measures such inequality on a global scale. Locations with a low HDI (<0.55) have a high vulnerability because many people lack basic needs of sufficient water and food even in ‘normal’ times. Much of the housing is informally constructed with no regard for hazard resilience and access to healthcare is poor, and disease and illness are common. Education levels are lower, so hazard perception and risk awareness is low. Low-income groups lack a ‘safety net’ after a disaster, either a personal one (e.g. savings, food stores) or a government one (e.g. social security, aid, free healthcare).

Other factors can influence vulnerability and resilience. Highly populated areas may be hard to evacuate, whereas isolated and poorly accessible areas can slow hinder rescue and relief efforts. In urbanised areas, the death tolls can be high because of the concentration of at-risk people. On the other hand, urban areas usually have more assets (hospitals, food stores and transport systems) than rural areas which can increase their resilience.

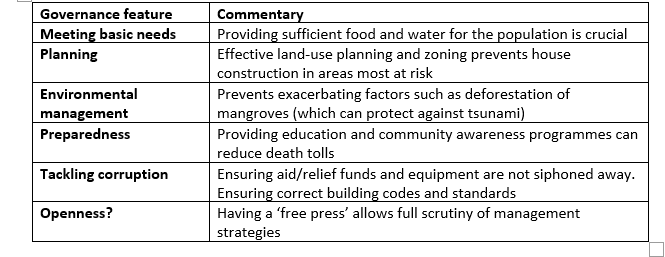

It is important to note that all of the above factors are dynamic and hence the safety of the people in a place is difficult to manage, and requires good governance. Table 1 illustrates some elements that constitute effective governance in a place.

Table 1. Elements of effective governance in building a place’s resilience

Attachment to place

The relationship between hazards and place also extends into the concepts of perceptions of place, representation of place and attachment to place. A simple reason why so many people are affected by a hazard, say from a volcano, is that they live there because they want to, or need to. They have a close bond (attachment) to that place for a variety of reasons.

Volcanoes can influence attachment to place according to the degree of risk posed by the volcano. This is often conveyed between several generations to influence an individual’s and a community’s perception and hence their emotional attachment to that volcano. For example, the community around Mount Merapi in Java (Indonesia) attach a great deal of cultural significance to living near a volcano - it is part of their identity. Merapi holds particular significance for Javanese beliefs; it is a sacred mountain. To keep the volcano quiet and to appease the spirits of the mountain, the Javanese regularly bring offerings. In addition, a spiritual guardian is appointed to ‘manage’ the mountain’s eruptions, not always successfully. In 2010, the then guardian Mbah Maridjan was killed by a pyroclastic flow as he placed offerings of rice and flowers around the volcano.

Volcanic eruptions have also influenced people’s activities around Mount Vesuvius near Naples, Italy. Two large eruptions thousands of years ago left thick deposits of tephra which have weathered to form rich, fertile soils. Consequently, this area is abundant for farming and there are also a number of tourist related economic activities. These include the tourist site of Pompeii, which owes its existence to a volcanic event. The Roman city was buried by an eruption in AD79, and it has subsequently been rediscovered and excavated. Hence it is a very popular tourist attraction and many people depend on it economically. Attachment to place here is therefore strong.

Elsewhere, Iceland utilises its tectonic activity for economic gain through tourism and geothermal energy and it is very much a part of the countries identity. The geothermal energy produced and associated tourist sites (e.g. geysers, volcanoes and geothermal spas) are integral to people’s daily lives and their way of supporting themselves, producing food (e.g. in greenhouses) and a source of revenue (e.g. tours, hotels etc.).

Conclusion

The connections between hazard and place are multiple. It might help to consider them in terms of how the place influences the impact of a hazardous event, the management of its aftermath, and the attitudes of people to living in such a potentially dangerous location.