[Inequality is a key concept within A Level Geography. Here’s one interpretation of the concept.]

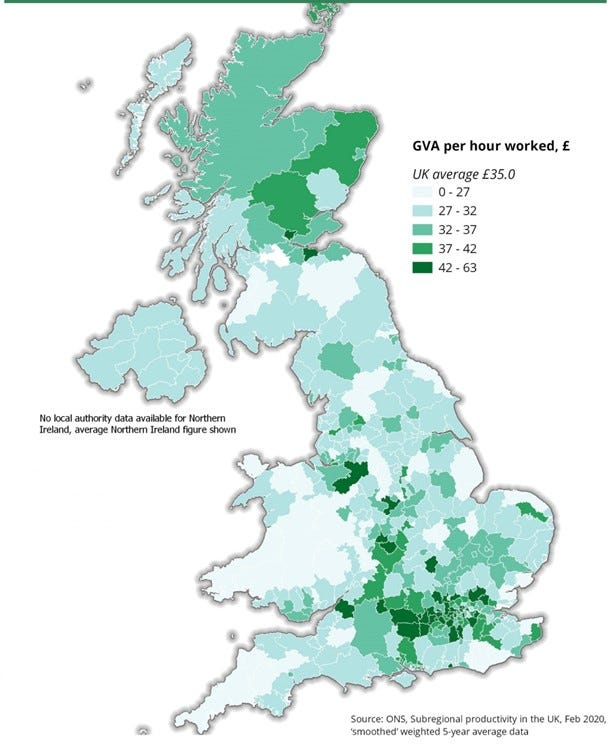

Figure 1. Productivity in the UK [Economic output (GVA) £ per hour by Local Authority] 2020

Source: House of Commons Library (2020)

The UK is one of the most regionally unequal countries in the developed world. Productivity in London is 75% above the national average. The western half of London (and areas immediately to the west further – the Thames Valley) are one of the richest and most productive regions in Europe, while much of the rest of the UK, especially the north of England and Wales, is as poor as Portugal or parts of eastern Europe. (Figure 1)

However, London also has the highest levels of child poverty in the UK, with half of the children in some boroughs living under the poverty line. Indeed, there are more poor children in the capital than in Scotland and Wales combined. Most Londoners are far from rich; after taking housing costs into account, the average household in London has an income slightly lower than the national average. Unemployment, too, is higher in London than elsewhere in the UK, and it was so before the Covid pandemic.

Other features of such inequality

Firstly, the rewards of the higher productivity in London are very unevenly distributed. The very highest earners in the country are overwhelmingly concentrated in London, pushing up average wages – but there are also hundreds of thousands of low-paid workers, as well as relatively high unemployment.

Secondly, housing (and other) costs are much higher in London, so London workers need to earn significantly more to have the same disposable incomes as workers elsewhere. Thirdly, whilst the UK tax and benefit system is generally redistributive, with high-earners paying more tax on their incomes – and much of that money is recycled by the state by public services, pensions, and other benefits – this happens at a national not local level. Therefore, much of London’s extra output is redistributed to the rest of the country, meaning that incomes, especially after housing costs, are much more equal than productivity.

Since 2010, inequality has been exacerbated by government policy. Cuts to benefits for low-income families and children, and housing benefits, have worsened child poverty nationally - especially in London - at the same time as pensions have been relatively protected. Furthermore, cuts to local authority spending have been concentrated on poor areas that relied most heavily on central government funding, hurting deprived areas of London and disadvantaged areas of the north. Although London has subsidised the rest of the country when it comes to benefits and public services, it hasn’t done so in terms of transport and infrastructure spending, which have been concentrated in the south-east - CrossRail and the HS2 development exemplify this. Between 2009 and 2019, the North received £349 per person in investment, whereas London received £864 per person.

What has caused the inequality?

The roots of inequality lie in the deindustrialisation of the 1970s and 1980s. The industrial heartlands of the north and Midlands, including former coal mining areas with associated heavy industries, were badly affected by this process. However, London also had a large light manufacturing sector. Its decline, and the closure of the docks to the east of the city, meant that London too lost hundreds of thousands of skilled manual jobs. Indeed, the population of inner London fell by more than a fifth in the 1970s.

London

London’s subsequent recovery and current prosperity was built on globalisation, immigration, and the dominance of the service sector, particularly finance and legal services. Often these services benefit from the economics of agglomeration, where their concentration in the city increases the size of the talent pool and makes them more productive. Linked to these are labour-intensive services that also benefit from agglomeration, but in a different way: they thrive because there are lots of people living and working in a densely populated area: restaurants, transport, and delivery services. However, the Covid pandemic hit these activities hard as many workers in the finance and legal services worked from home. Part-time office occupancy is still widespread in the city causing substantial loss of revenue for the owners of office buildings, as well as many empty floors within them.

The economy in London is very productive overall, but also very unequal – and very dependent on inward immigration, both domestically and internationally, of younger workers. It has also led to an increasingly two-tier labour market, characterised by insecurity and ‘zero-hours’ freelance work, especially for the young, not just in services such as delivery and taxis, but also in some professional occupations such as journalism and the arts.

Furthermore, the centre of government, and the civil service, is concentrated in London. Only one in seven Londoners works in the public sector, compared with more than one in five in the north-east (and more than one in four in Northern Ireland). However, public sector pay within London is considerably more generous relative to the private sector outside London.

Outside London

The growth in manufacturing productivity means that far fewer skilled workers are required to produce the same amount of goods. Even in the areas of the country that remain most dependent on manufacturing, far more people work in services; in no economic region does manufacturing account for much more than one job in 10. However, those jobs are – especially outside of some successful large cities – on average considerably less productive than in London and its periphery.

Having said this, national employment rates are at historically very high levels, even in the most deprived areas of the country – but they are different jobs to those of the 1970s and 80s. They are much more likely to be in the service sector, much more likely to be done by women, low-paid and often less secure.

‘Levelling-up’?

The above suggests that the key driver of economic development in the UK has been the shift from manufacturing to services, and the growth of the high productivity service sector. This, in turn, is both driven by, and requires, the expansion of the graduate labour force and its increasing concentration in London, other large cities, and commuting areas around them. Furthermore, this then generates many low productivity service-sector jobs, albeit insecure for many. This applies to the whole country, driven by technological changes that are likely to intensify, not reverse, over coming decades.

This doesn’t mean that growing inequality is inevitable. Reversing it requires national and local government policies addressed at people and places – the term used by the Johnson Conservative government after the 2019 election for this process is ‘Levelling-up’. Investment is needed in connectivity (physical and digital) that allows skilled workers to have productive, well-paid jobs wherever they live. Investment is also required in people, narrowing the divide in skills and productivity between those who go to university and those who don’t. None of this will be cheap or easy – but ‘Levelling-up’ will only work if it is about all the UK, and about people and places.

Levelling-up in the UK should be apolitical - it is in everyone's interest. Odd that it is far from apolitical.