Is globalisation being rebranded?

Decoupling, re-shoring, near-shoring, and ally-shoring (and an EV extra)

[In the light of recent political events in the USA, I thought it appropriate to post an edited version of the piece I wrote in September 2024’s Geography Review. This can act as a base for what happens next to Global systems after January 20th 2025.

Someone recently posted on social media, ‘Don’t deal with an American unless he/she is accompanied by a responsible adult’. Today’s appointment of Elon Musk to the DOGE (Department of Government Efficiency) possibly reinforces that view.

Finally, geography teachers will find a growing community on BlueSky, having left Xitter.]

Introduction

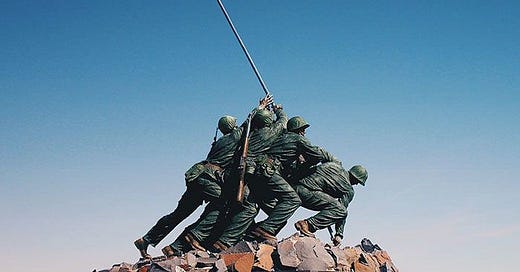

In 2023 the value of USA imports of goods from China fell by over 20% compared to the previous year. This was part of a trend that had started in 2019, with small increases in imports from other Asian countries including India, Japan, Thailand, and Vietnam, together with slightly larger increases from Mexico during that time-period [Figure 1.] Similar trends have also been experienced by European Union (EU) countries with imports from China falling by 10% in 2023 compared to 2022. The reasons for these trends are captured by the concepts of decoupling, re-shoring, near-shoring, and ally-shoring [Box 1].

Figure 1

Source: US Census Bureau

Box 1.

Re-shoring is the process of bringing back production activities from overseas locations to the home country. Re-shoring can have various benefits, such as reducing logistics costs, increasing flexibility of production, enhancing customer service, and strengthening the local economy. Re—shoring can be motivated by strategic factors, such as protecting intellectual property, reducing risk, and responding to changing customer preferences.

Near-shoring is a strategy that involves a manufacturing company transferring all or part of its operations to a nearby country. The purpose is to take advantage of lower costs while maintaining proximity to the home country, often one that shares a border with the home country. Near-shoring can have several benefits, including lower costs, similar time zones, and cultural similarities. Mexico and Colombia are popular nearshore locations for US-based industries.

Ally-shoring refers to the process of sourcing essential materials, goods, and services among trusted democratic partners and allies. It is a version of nearshoring in that greater collaboration between companies takes places due to a mutual sense of being part of a similar political system which leads to connections in terms of R&D, trade, security of information, and better governance.

Decoupling is the term for the outcome of all the above, with (in this case) the US economy being less dependent on China.

Changing geopolitics and systems

Global economic systems are changing. We have become familiar with the terms of out-sourcing and off-shoring, whereby TNCs manufacture or assemble goods in a country which is geographically separate from, and less ‘developed’ than, the home country to reduce costs through cheaper labour. For many decades, China was the go-to place for such production of industrial parts, materials, machinery, and consumer goods.

Today, new processes are emerging, notably re-shoring, near-shoring, and ally-shoring (or friend-shoring). The Americans collectively call these processes ‘decoupling’. All these processes have been accelerated following the Russian invasion in Ukraine and the ‘sabre-rattling’ by the Chinese navy in the South China Sea. Some argue that Russian President Putin’s actions in Ukraine have encouraged the Chinese Premier Xi Jinping to be more aggressive towards Taiwan – an island off the east coast of China that the latter regards as being part of its territory. The war in Gaza between Hamas and Israel begun in October 2023 has also added greatly to geopolitical instability in the world.

As shown in Figure 1, decoupling began in earnest in 2019. A 2017 EU survey found that over 60% of European and US manufacturing companies expected to re-shore some of their China-based production in the coming years. The survey revealed that the most common host countries for re-shoring were other Asian countries (e.g. Vietnam and Thailand), followed by western and eastern European countries, such as Czechia, Poland, and Hungary. For production that was expected to re-shore to North America, the USA is the leading location, followed by Mexico (see below).

US-China decoupling

Initiated by President Trump, and continued by President Biden, there’s now a broad consensus in US policy-making circles that global, and especially American, supply chains need to become less dependent on China. It’s seen as a bad idea to have so many manufactured goods being made in China because there are concerns about increasing Chinese military capabilities, with potential risk of restrictions on critical imports, such as rare earth metals, in times of geopolitical crisis. So, from tariffs and sanctions introduced by President Trump to President Biden’s ‘friend-shoring’ initiatives under the Inflation Reduction Act, including subsidies for key industries, US companies have been encouraged to either make things domestically or import them from countries other than China.

However, the above measures aren’t bringing resilience or security to global supply chains. America’s and the West’s reliance on Chinese products remains. Some economists state that because many of the manufactured goods exported to Western countries from places such as Vietnam and Cambodia contain a lot of parts and components made in China, such decoupling is ‘phoney’. For example, the magazine The Economist wrote:

‘America may be redirecting its demand from China to other countries. But production in those places now relies more on Chinese inputs than ever. As South-East Asia’s exports to America have risen, for instance, its imports of intermediate inputs from China have exploded. China’s exports of car parts to Mexico, another country that has benefited from American de-risking, have doubled over the past five years.’

One area of concern is that of critical technologies. The US has a stated aim to remain at the top of the global pecking order of these industries. It needs to ensure key components such as semiconductors, electric vehicles, batteries, and solar panels have at least some footprints on American soil to avoid pandemic-era-like shocks to supply chains and any vulnerabilities resulting from other unforeseen events.

Furthermore, there is impact of ‘Industry 4.0’ on re-shoring decisions. Industry 4.0 refers to the digital transformation of manufacturing, which involves the use of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, robotics, cloud computing and big data. Industry 4.0 increases automation and productivity and enables more customised and flexible production. It also creates more attractive production conditions in the home country thereby facilitating re-shoring.

A near-shore country - Mexico

Skilled labour shortages in the US have been a growing problem for several years, caused by an ageing workforce. It is stated that 25% of manufacturing workers in the USA are 55 or older. In contrast, a survey of two large industrial estates in northern Mexico which each had over 5,000 workers found that they had an average age of only 27.

Consequently, manufacturing in Mexico continues to increase. Near-shoring in Mexico is an attractive prospect for many US manufacturing companies. In early 2023, total Mexican manufactured goods exports rose by almost 6% compared to the same period in 2022 to a total of $53 billion. Manufactured goods now make up almost 90% of Mexican exports, much of which are cars and car components.

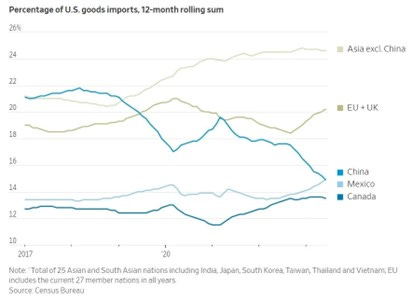

The northern states of Mexico have become an even more a favoured location for US manufacturing companies. Companies here include P&G, Honeywell, Johnson & Johnson, Ford, Nissan, Toyota, LG, and Whirlpool. Interestingly, several Chinese companies are following suit and are establishing here, seeking to avoid direct US tariffs. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Mexico – distribution of industrial parks

Source: Bloomberg 2023

A specific industry - the clothing industry

Global clothing and footwear TNCs such as Adidas, Nike and Primark have been shifting some of their supply chains out of China in recent years (see Figure 3 for import origin data for the USA). These moves were initially driven by lower operating costs but have been pushed increasingly by mounting geopolitical tensions between China and the west. Having said that, China remains the world’s top clothing exporter – currently about one-third of all garments globally still come from its factories.

Several US and European clothing brands say they want to cut ties with China even further. However, finding new production locations elsewhere brings challenges: a lack of skilled workers, insufficient raw materials, or underdeveloped infrastructure and logistics networks. Accessing components also plays a key role - the Vietnamese clothing industry, for example, relies on Chinese-made buttons, thread, labels, and packaging, with only about 30% of such materials made domestically. Moving production away from China will increase costs.

Figure 3. The diversification of the USA’s sources of clothing (2017-2023)

What of the UK?

The Conservative government of Rishi Sunak did not openly adopt a formal decoupling policy, though it wanted to keep as much manufacturing industry, especially the high-tech industry, onshore. The UK has an unbalanced economy. The long-term trend is a growing weakness in exporting manufactured goods (reflecting a decreasing manufacturing base) and increasing services (including exports) (see Figure 4).

The UK has an increasingly services-led economy. Although it does excel in certain manufacturing industries (for example, aerospace and high-end cars), it does not have the broad-based high-value manufacturing infrastructure of, for example, Germany. It would be very hard to redevelop this, and the associated supply chains, sufficiently to reverse this long-standing trend.

As in the USA, Rishi Sunak sought to protect the UK’s critical technology industry. In November 2023, the government announced its ‘Advanced Manufacturing Plan’ that includes £2 billion in funding for the motor vehicle industry and £975 million for the aerospace industry. According to the plan, domestic industry making EV batteries could employ 100,000 workers by 2040. This built on previous announcements by Nissan Motor to invest £2 billion to expand its UK electric-vehicle hub in Sunderland; by Tata Motors to construct a £4 billion gigafactory in Somerset; and by Airbus to invest more than £100 million at its plant near Chester.

The Sunak government also planned several investment zones that will each receive £160 million over 10 years in areas such as South Yorkshire, Greater Manchester, East Midlands, West Midlands, and the Northeast. In addition, the chancellor of the exchequer Jeremy Hunt announced the government will extend from 5 to 10 years the financial incentives for these investment zones and tax relief for the country’s 12 freeports. Economic development through freeports had been espoused by the Sunak government but so far, they haven’t lived up to the hype or levels of investment needed.

Figure 4. The UK trade balance (1997-2023)

Source: Statista

Conclusion

China is the biggest trading partner for over 120 countries, and so it remains a crucial driver of economic growth for a large portion of the world’s economy. Even for the US, China is still one of its three biggest trading partners, a backdrop against which both sides are increasingly engaged to avoid an ‘eastern Cold War’ that would weigh heavily on their economies. This underscores the challenge of weaning itself and the rest of the world from China’s influence. Nevertheless, economic globalisation is changing. Decoupling will lead to decreasing, rather than increasing, economic integration of countries, and reduced movement of goods, services, and capital across borders. Politically, it also raises fears of protectionism and nationalism.

And an extra….

Electric vehicles from China

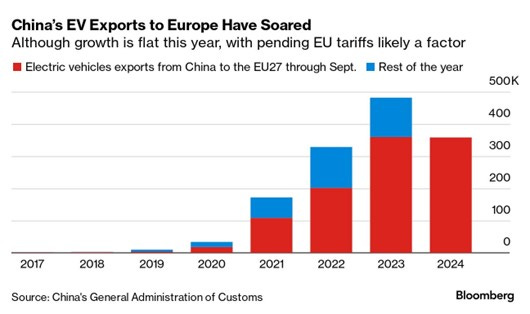

In 2023, China became the world’s foremost exporter of cars, with more than 5 million sales overseas. The rapid emergence of electric vehicle (EV) manufacturing in China is sending shockwaves across the global automotive industry.

This expansion has added fuel to clashes between China and the USA over trade and technology. Competition between these superpowers has become intense. Chinese EVs are now seen as a serious threat by US politicians and car manufacturers. President Biden has placed large tariffs on EVs imported from China, seeing them as a threat to US jobs and national security. Recently elected President Trump has stated that he will introduce 110% tariffs on these cars in 2025.

The EV industry in America and in Europe is under pressure from falling sales, political pushback on net zero targets, and fierce competition. China’s EVs are getting cheaper, while the reverse is happening in Europe and the USA. Tesla reported falls in profit in the first quarter of 2024 and announced it would cut 10% of its 140,000 workforces.

The growth of EV production in China has been spectacular. In April 2024, sales of EVs and plug-in hybrids accounted for more than half of new car sales in China for the first time. The largest EV car producer in China is BYD (Build Your Dreams).

EU-China EV trade

After months of negotiations, threats of retaliation and auto-industry lobbying, the European Union has imposed higher tariffs of up to 45% on electric vehicles from China. The move risks ratcheting up trade tensions between the world’s biggest exporters. Although talks between China and the EU will continue even after the new tariffs take effect, some Chinese producers don’t seem deterred.

A big question is how China will respond. So far, while it has threatened to curb investments in Europe, Beijing has mostly acted within the bounds of WTO rules, opening investigations of its own into dairy, pork and brandy exports from the EU as well as warning it could return tariffs on cars with large engines to 2018 levels. The concern in Europe is that China will start taking other, more punitive actions such as restricting critical exports like rare earths needed to make EV batteries.

Thank you. Good to know it helps.

This is great for the A levellers and their use of up to date language in the examination showing their wider reading. As such I have shared this with my networks on X and on Linkedin. Thanks David.