[This week the number of subscribers here passed 2,250. Thank you and welcome to all. This post provides an update on the population of the second largest (by population) country (after India) in the world.

For those wondering, I will return to an example of an exam question and an assessed answer (AO1 v. AO2) on another topic soon.]

A set of quadruplets in China

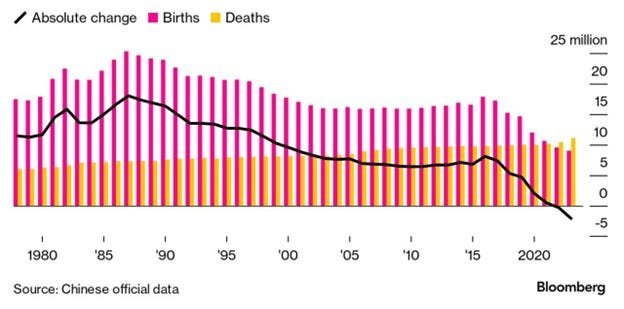

In 2023, China’s population fell by 2 million, a trend that looks set to continue given that the number of babies born also hit a record low (Figure 1). The country’s fertility rate, which has already fallen below replacement levels decades ago, fell to only 1.09 - one of the lowest rates in the world, and even lower than that of Japan.

Chinese authorities are seeking to rectify this issue, offering couples incentives to have another child and expanding public health insurance to cover reproductive services.

Figure 1. China: Population change 1978 - 2023

At the older end of the age spectrum, the retirement age has been kept at 60 for men and 55 for women for more than four decades – one of the lowest levels in the world. Increasing that threshold would reduce the speed at which the working-age population shrinks and give the government more time to work out how to boost birth rates.

Impact on the Chinese economy

The Wall Street Journal reported recently:

‘As the population peaks, China is showing signs of Japanification’. Yin Jianfeng, deputy director of the National Institution for Finance and Development, stated in June 2024. Yin urged the Chinese government to spend more on child rearing and education to avoid the fate of Japan, which has experienced decades of stagnation.

The Economist wrote:

China’s economy risks shrinking, too, as a result. With an enormous burden of care on the horizon, the government senses an impending disaster. China is getting old before it gets rich. In 2008, when Japan’s population started to fall, its GDP per person was already about $47,500 in today’s dollars. China’s is just $21,000. As more of that money is spent on protecting ageing citizens, less of it will be available for the working generation to consume or invest.

Some economists suggest that the population reduction in China can lead to a ‘doom loop’. As lower productivity begins to affect production, China may be compelled to increase imports to satisfy demand in those industries. This could significantly affect innovation and entrepreneurship which in turn can further reduce productivity. They suggest that size of the workforce affects innovation because as the number of employed individuals shrinks, the pool of new ideas becomes narrower. If population growth falls to zero or becomes negative, then the knowledge behind those ideas stagnates.

The shrinking of a population is not in itself a problem – it is the ageing of that population. Rising old-age dependency ratios put a significant economic burden on working people, and an ageing workforce probably does reduce innovation and productivity growth.

China has a baby bulge coming

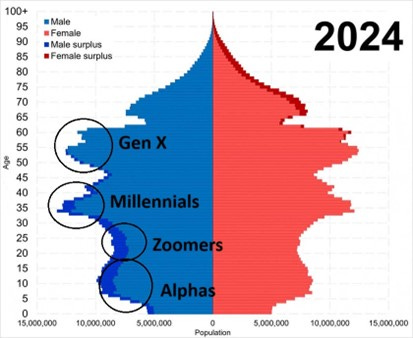

China has a large generation of young people, currently aged 5 to 15, that may relieve demographic pressure in the coming years – Figure 2.

Figure 2. China – population pyramid 2024

China’s current young working generation - the ‘Zoomers’ - are a small generation due to the latter stages of the Chinese one-child policy. However, the generation younger than that - the Alphas - are a larger generation. China’s Alphas are not a true ‘baby boom’ as there was no surge in fertility rates 5 to 15 years ago. Rather, the Alphas are a demographic echo of the large ‘Millennial’ generation, which is itself an echo of China’s extremely large baby boom generation (Gen X).

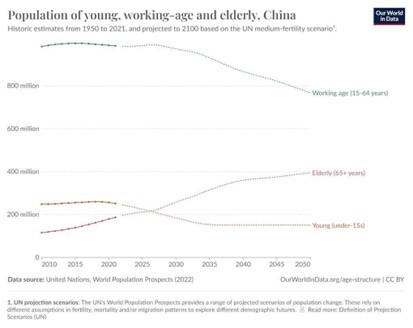

As the Alphas reach working age over the next decade, they will stabilise China’s demography. China’s working-age population is projected to increase over the next few years, before beginning a slow decline (Figure 3).

Figure 3. China – population trends 2010 - 2050

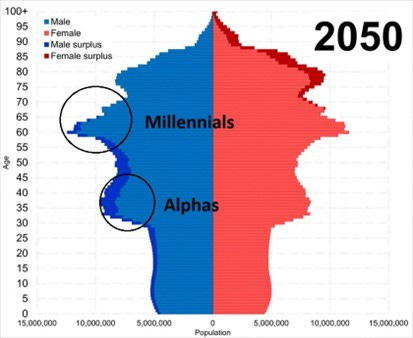

An ageing population will not be a problem for China’s economy until the mid-21st century. But from 2050, things start to look problematic. China’s large millennial generation will begin to age, and there will not be a large young cohort to replace them (Figure 4).

Figure 4. China – population pyramid 2050 (predicted)

This prediction assumes that the recent post-Covid pandemic fall in Chinese fertility rates does not bounce back within the next decade. Even though the impact of China’s demography does not get severe until 2050, it will still experience gentle ageing over the next 25 years. Its median age is projected to rise from 39.5 to 50.7. After 2030, China’s working-age population will start to decline, and its dependency ratio will start to increase.

How does China respond to this challenge?

Firstly, it could raise the retirement age. Simply increasing this to 65 will decrease the dependency ratio significantly and reduce the burden on working people. Secondly, it has already increased rates of enrolment of post-secondary school education. In 2010, only 26% of college-aged Chinese people were enrolled in post-secondary education; by 2023 it was over 60%. A better-educated workforce is a more productive workforce. The Chinese workers that will retire over the next quarter century - the Gen Xers and older Millennials (Figure 2) - are not highly educated. The workers that will replace them - the Alphas - are highly educated. That may compensate for much of the loss of working-age population.

Anytime, not FT but another good source.

Stephen Schwab

@schwabs52

·

Aug 27

China's kindergarten closures foreshadow economic hit from falling births https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Asia-Insight/China-s-kindergarten-closures-foreshadow-economic-hit-from-falling-births via

@NikkeiAsia