[Welcome to new subscribers. Along with everyone else, can I recommend you make use of the Substack app (on phone, tablet and laptop) for high quality reading? This post obviously links to climate change – at a time when a climate-change denier has been re-elected, worryingly.

Accordingly, can I also recommend an excellent new podcast from Hannah Ritchie (and her Substack ‘Sustainability by numbers’) and Rob Stewart to be found here ? The second episode, with Sir David King, examines shrinking levels of Arctic Sea ice, and proposes several solutions, one of which involves whale poo.]

The Arctic

Arctic sea ice retreated to near all-time low levels in the Northern Hemisphere in the summer of 2024, melting to its minimum extent for the year on September 11, 2024, according to researchers at NASA and the National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC). The decline continues the decades-long trend of shrinking and thinning ice cover in the Arctic Ocean.

The amount of frozen seawater in the Arctic fluctuates during the year as the ice thaws and regrows between seasons. Over the past 46 years, satellites have observed persistent trends of more melting in the summer and less ice formation in the winter. Tracking sea ice changes in real time has revealed several impacts, from losses and changes in polar wildlife habitat to impacts on local communities in the Arctic and international trade routes.

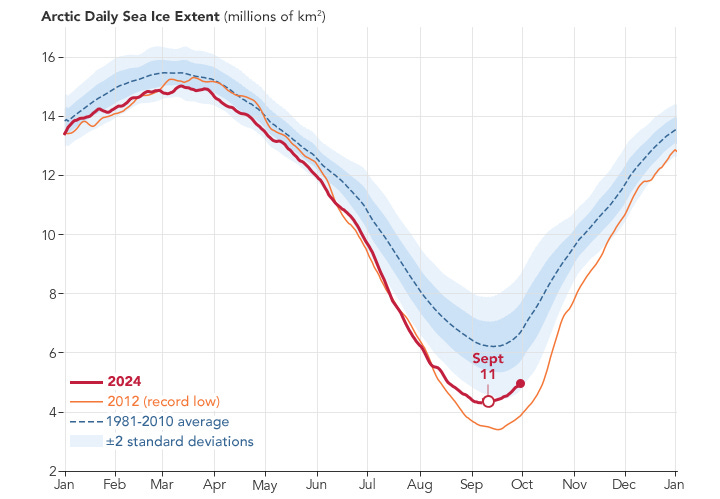

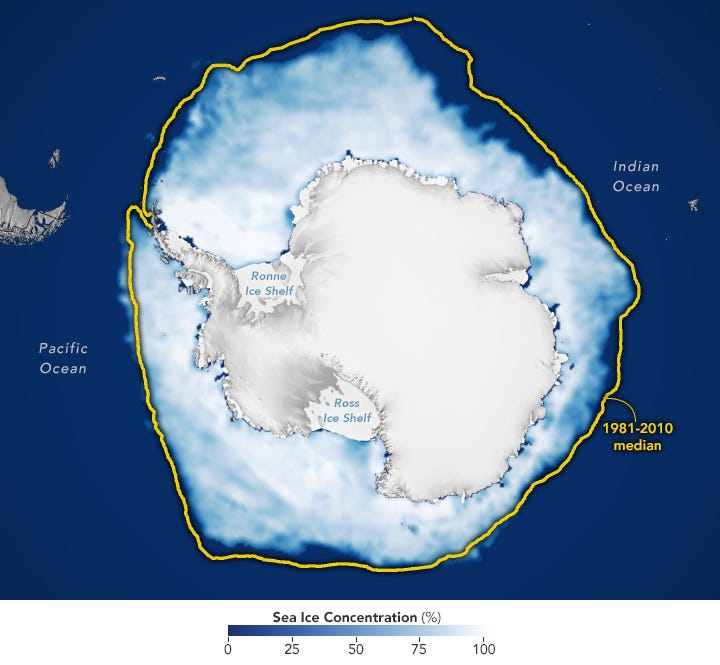

This year, Arctic Sea ice shrank to a minimum extent of 4.28 million km2, as shown on the map below (Figure 1). That is 1.94 million km2 below the 1981 to 2010 end-of-summer average of 6.22 million km2 (Figure 2). The difference in ice cover spans an area larger than the state of Alaska. The lowest was in September 2012. [Sea ice extent is defined as the total area of the ocean with at least 15% ice concentration.]

Figure 1 Arctic Sea Ice (September 2024)

(Yellow line = 1981-2010 median)

Figure 2. Variations in Arctic daily sea ice extent

Sea ice is not only shrinking, but also getting younger and thinner. Ice thickness measurements collected with spaceborne altimeters have found that much of the oldest, thickest ice has already been lost. Ice in the central Arctic, away from the coasts, now hovers around 1.3m thick, down from a peak of 2.7m in 1980.

The Antarctic

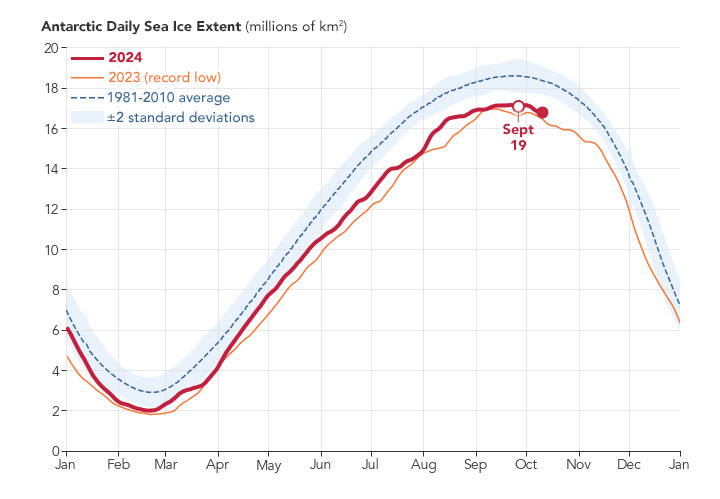

Sea ice in the southern polar regions of the planet was also low in 2024. Around Antarctica, scientists tracked near-record-low sea ice at a time when it would have thought to be growing extensively during the Southern Hemisphere’s darkest and coldest months. Ice around the continent likely reached its maximum extent for the year on September 19, 2024, when growth stalled at 17.16 million km2. This year’s maximum, shown on Figure 3, was the second lowest on record but remained above the record winter low of 16.96 million km2 in September 2023. The average maximum extent between 1981 and 2010 was 18.71 million km2.

The meagre growth in 2024 prolongs a recent downward trend (Figure 4). Prior to 2014, sea ice in the Antarctic was increasing slightly by about 1% per decade. Following a peak in 2014, ice growth has fallen dramatically. The recurring loss hints at a long-term change in conditions in the Southern Ocean, likely resulting from global climate change.

Figure 3 Antarctic Sea Ice (September 2024)

Figure 4. Variations in Antarctic daily sea ice extent

In both the Arctic and Antarctic, positive feedback mechanisms operate, i.e. ice loss compounds ice loss. This is because while bright sea ice reflects most of the Sun’s energy back to space, open ocean water absorbs 90% of it (i.e. varying albedo rates). With more of the ocean exposed to sunlight, water temperatures rise, further delaying sea ice growth. Overall, the loss of sea ice increases heat in the Arctic, where temperatures have risen about four times the global average.

You can download the satellite images shown here.

And, another story from Antarctica…

Walking down a beach in Denmark (near Perth), Australia, a malnourished Emperor penguin was found - 3380 km away from its home in Antarctica. Scientists are shocked by this event because this is the furthest north an Emperor penguin is documented to have travelled.

Emperor penguins often travel on sea ice to look for food. However, due to climate change there are fewer icebergs to migrate on. It is likely that the penguin followed an ocean current north from Antarctica.

Emperor penguins are only found in the wild in Antarctica.