Sexual violence in India

Rape, and for the women of India, there are even dangers in going to the toilet.

[Hello to the new subscribers on here. This is a post about sexual violence in India – an indicator of social and cultural development.

But before that, you will be aware of the tragedy that affected the superyacht Bayesian in the waters off the northern coast of Sicily. The event dominated the western news media far more than the 3000 people who die in the Mediterranean each year, and more than the regular drownings of ‘boat people’ in the English Channel. Every such death is tragic. I posted on ‘Xitter’ a link to this interesting ‘take’ on the Bayesian written on Substack by the political economist Ann Pettifor, linking the event to inequality and climate change, here. Due to the childish nature of Mr Musk, who has fallen out with Substack, the post seemed to disappear. I am slowly moving over to Bluesky, if you want to follow me there.

As an aside, if you are an economics student, then I strongly recommend you subscribe to Ann’s Substack.]

In August 2024, thousands of doctors in India went on strike in protest over the brutal rape and murder of a trainee doctor while on shift at a Kolkata hospital. Protesters demanded justice for the victim and stronger legislation to protect healthcare workers from violence. The 31-year-old doctor in Kolkata's state-run RG Kar Medical College was found raped and murdered on August 9. A police volunteer was subsequently arrested in connection with the crime.

Doctors in India's overcrowded government hospitals protested being overworked and underpaid and say not enough is done to curb violence leveled at them by people angered over the medical care offered. Women - who make up nearly 30% of India's doctors and 80% of the nursing staff - are more vulnerable than their male colleagues. Medical associations are calling for a stringent federal law to protect healthcare workers and an overhaul of security measures at hospitals, including video surveillance and deployment of additional security staff.

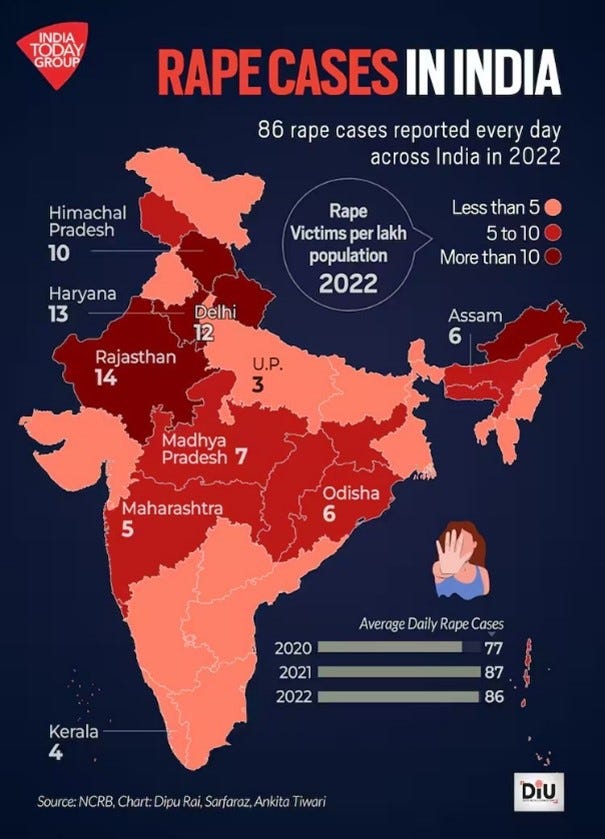

Figure 1. Rape cases in India

[In 2016, I wrote an article about sexual violence in the country. Here is an amended version:]

During May 2014, the dangers faced by women going to the toilet outdoors in rural India were made starkly clear when two teenage girls were ambushed, gang-raped and hanged from a tree. The incident received international media coverage, with universal horror. In November 2014 another incident took place where a 15-year-old girl was set on fire after she had been molested.

These events were not the first time that the world was outraged by incidents of sexual violence in India. In December 2012, in New Delhi, a 23-year-old physiotherapy student was on a bus heading back from the cinema with a male friend. Police said that the driver and at least five other drunken men dragged her to the back of the bus, raped her, and beat up her friend. When they were done, they dumped the victims by the side of the road; the raped woman died from her injuries two weeks later at a hospital in Singapore

Rape is not a crime unique to India – indeed the numbers of reported rapes are well below those in the USA and most European countries. Figure 1 provides a map of the distribution of this crime in India, in 2022, based on reported incidents. (This does not include unreported cases of both rape and other forms of female abuse.)

Each of the above cases caused outrage within India, with protest marches involving huge numbers of people taking place in Delhi and across the country. A significant amount of pressure has been placed upon Indian politicians to deal with the contributory factors, such as low levels of women’s rights and inadequate sanitation, especially in rural areas. They have also faced pressure to be more punitive – in March 2014 a new act was passed containing harsher penalties for crimes against women including the death penalty for rapists.

The daily walk

In many Indian villages the women walk out to the fields twice a day – at dawn and at dusk. The surrounding fields are the only toilet most of them have even known. In most villages across India only 10% have their own private facilities, and almost none has suitable sewage systems to remove the waste. The women walk out together in groups, for safety. Once away from the village they separate and space out for a little privacy. Darkness gives the women cover, and a degree of privacy, but in some ways it makes them more vulnerable. The women usually carry a small bottle of water to assist with their cleansing. No toilet paper is used.

In most rural villages there is a convention that the men go to the toilet only at dawn, but boys and young men sometimes break this rule to harass or molest the girls and women. There are accounts of women being subject to catcalling and groping (an activity known as ‘eve teasing’), though individuals usually do not admit that it has happened to them (only to others). Girls are brought up to shout and be aggressive if a boy comes near them. After the dawn visit, there is the long wait until the next trip to the open-air toilet after darkness, some 14 to 15 hours later. Women often have no choice but to contain the desire to urinate or defecate for hours on end and face considerable daily discomfort as a result.

In the fields, it is important to tread carefully. Once the crops are cut and the fields are bare, the whole ground space is open for anyone to use. It is literally an open toilet. During sowing and harvesting, the fields are out of bounds. Then people must walk for another 15 minutes, to an uncultivated area. The exercise that normally takes 45 minutes to an hour stretches to an hour and 15 minutes, or more.

What are the contributory factors?

Poverty is clearly a major driver. More than half a billion Indians lack access to basic sanitation. Most do not have access to flush toilets or other latrines. A recent study by the global health organisation Population Service International (PSI) and Monitor Deloitte stated that Bihar had India's poorest sanitation indicators, with 85% of rural households having no access to toilets. The police in Bihar State reported 870 cases of rape in 2013, most of them taking place during the early morning and early evening.

The PSI report added that 49% of the households that did not have a toilet wanted one for ‘safety and security’, another 45% wanted a toilet for ‘convenience’, while 4% wanted one for ‘privacy’. Surprisingly, only 1% indicated ‘health’ as a motivator for having a toilet. The Bihar state government says it plans to provide toilets to more than 10 million households in the state by 2022 under a federal scheme. A law making toilets mandatory has been introduced in several Indian states as part of the ‘sanitation for all’ drive by the Indian government. Special funds are made available for people to construct toilets to promote hygiene and eradicate the practice of faeces collection, which is mainly carried out by low-caste people.

However, another factor is one of attitude. Most villagers possess metal toilet pans within their houses. These tend to be reserved for times of illness, emergency or for older people. Women complain that they are hard to disinfect, and they are often thrown away after they begin to smell. Many people consider open-air toilets as the natural way of defecation. Enclosed toilets are considered to be a product of modern living, and not an expectation or entitlement – they are a preserve of the rich. It has been reported that at the only school in Kurmaali, a village in the state of Uttar Pradesh, where there are 300-day pupils, the two toilets are generally not used: one had no door; the other was full of bricks and other rubbish. When one of the school governors was asked why this was the case, he questioned why anyone would need a toilet. The school was right next to the fields, he pointed out.

What of the men?

Most of the men in rural villages work as daily labourers, drivers or farmworkers, or they are unemployed. The lack of a toilet does not usually bother Indian men – the view is that they can ‘go anywhere’. The provision of a domestic toilet must be paid for from their wages. A simple toilet with a 10-foot-deep pit can cost around 10,000 rupees (£100). Even in the cities, it is common to see men urinating in public against a wall.

Back in Kurmaali it is interesting to note how the families spend their limited incomes. The streets are dotted with motorbikes and the occasional car, luxury items mostly acquired as part of a dowry. A key purchase is often a television set and a satellite dish – even though the electricity comes on for only four hours every day at most. For many women, they consider themselves fortunate if their husbands treat them well and they do not drink alcohol or abuse them physically, so a toilet is not a priority.

A related problem

Poor menstrual hygiene in India has a significant impact on health and the environment. According to the charity the Kiawah Trust, supported by the US Agency of International Development (USAID), the incidence of reproductive tract infections is 70% more common amongst women who use unhygienic materials during menstruation. They say the lack of toilets and water at schools has forced 24% of girls to drop out of school as 66% of schools lack functioning toilets and access to water. A woman in India typically throws away 125-150 kg of mostly non-biodegradable absorbents every year, causing irreversible pollution. The same survey states that 88% of menstruating women do not have access to sanitary napkins and use alternatives such as sand, ash, cloth, dried leaves, hay and plastic. Sadly, for most of them these conditions are just a way of life.

Why is the sanitation problem so great in India?

It is a matter for debate as to why India suffers more severely in its incidence of outside defecation than much poorer countries, such as Congo or Afghanistan, or than other South Asian countries, such as Bangladesh (Figure 2). One reason could be political leadership: for too long India’s government failed to make sanitation and the building of latrines a public health priority. India’s new government now plans to build 130 million latrines by 2019. A second and more controversial reason could be the influence of traditional Hindu culture on sanitation habits. Studies of India’s population show strikingly higher rates of open defecation in Hindu-dominated villages compared with Muslim ones, despite the lower incomes, education and worse water supplies of Muslims. Some ancient Hindu texts state that distance should be maintained between faeces and human habitation, so it may be the case that many people take this teaching literally. If so, then a good way to get India’s sanitation closer to global standards would be to begin with an education campaign to persuade households to build – and use – their own latrines.

Figure 2 Global pattern of defecating in the open (people per km2), 2012

Conclusion

The recent tragic cases of sexual violence in India have brought the issues surrounding women’s rights to the surface. These include attitudes to women by men in a largely male-dominated society, domestic and public health and sanitation provision, and the role of the police and judiciary in protecting women. India is a rapidly emerging economy, generating significant levels of wealth for some of its people who are becoming increasingly sophisticated, with modern ways of thinking and access to modern facilities. However, as this article highlights, huge social disparities continue to exist in such a large and populous country.