Recent political events regarding immigration have highlighted one aspect of identity that has surprised many people. Why did so many people of immigrant extraction not only vote for Brexit, but also appear, in the guise of Rishi Sunak, Priti Patel and Suella Braverman, to be so supportive of restricting further immigration into the country that so warmly accepted their parents?

To many, these individuals are ‘going against their own interests’ by endorsing campaigns which have fanned the flames of xenophobia and pushed the country’s political leadership to the populist right. It is clear in seeking to answer this conundrum, the assumptions many of White British people, like me, make, cannot, and should not, be made.

The writer and journalist Hardeep Matharu, editor of the Byline Times, has written extensively about this issue. She writes that for her parents, ‘Britain has given them so much. After 50 years here, they don’t feel ‘other’ or like ‘immigrants’ but … ‘more British than the British’. They respect the UK for its opportunities to better themselves and the lives of their children, and this has inevitably shaped their political views. Hard work, aspiration and integration have all been key. Seen through their eyes, Brexit was a patriotic expression of what Britain ‘needed to get back to’’.

As with the parents of Sunak, Patel and Braverman, shadows of the imperial past are ever present for Matharu’s parents. They all share the fact that they grew up in colonial British East Africa, with both Sunak’s and Braverman’s fathers coming from present-day Kenya (Sunak’s mother came from the then Tanganyika), and Patel’s from Uganda. In these times and places, societies were strictly stratified. People of Indian extraction were middle-class, ‘below’ their white rulers, with colour bars operating to keep them apart, but ‘above’ the black Kenyan/Ugandan majority whose country it was.

The author Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, also from Uganda, states that Asian families in East Africa at that time would have benefited from the specific dynamics of the ‘divide and rule’ imperialism that existed. For some Asians, this included an inability to ‘tolerate black rule’ - something she states can be a taboo to even mention today. She states that these migrants to Britain were people ‘who were attached to the Empire and had attachments of empire’, when describing Sunak’s family and other families like his.

Deeper historical ties and identities exist though. Matharu writes ‘But, despite my father’s affinity with Britain, coming to a UK simmering with racial tensions in the 1960s was still tough. In reality, the impact of migration and a sense of ‘otherness’ never completely leaves you. The exploitation of countries like India and Kenya by the Empire, and brutality such as the 1919 Amritsar Massacre - which exposed the darkness around Britain’s ‘civilising mission’ - also hung heavy.’

These deep feelings of allegiance to the Crown, and of having suffered to get to and live here, are what may drive their hostility to other migrants, albeit from a much closer geographical and ethnic background to the ‘home’ population. People from the former colonies of India and East Africa had fought for Britain in two world wars and had helped rebuild the country. Why should Europeans exercising their freedom of movement, who had not faced the adversity of their generation or have historic ties to the UK like they did, be prioritised?

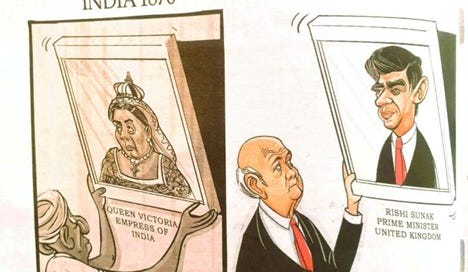

The influence of the ‘home country’ should also not be underestimated. One TV station in India described Sunak’s appointment as UK Prime Minister as ‘Indian son rises over the Empire; history comes full circle in Britain’. A cartoon in an Indian newspaper showed a portrait of Sunak taking its place next to one of the former Empress of India, Queen Victoria. For many Indians and people of Indian extraction, in the UK and around the world, Sunak’s appointment was a big moment.

Political choices are representative of our lives and experiences. They can also show how people can defy expectations because identity is more complicated than some of us may think. We can have multiple, conflicting, and changing strands in our conception of who we are; affiliations which don’t necessarily conform to pre-conceived ideas. The pursuit of populist politics and ‘them versus us’ social media soundbites, are making it increasingly difficult to live in a pluralistic society. We won’t always agree with others – shaped as we are by our own lived experiences – but hopefully in most people we can usually find some point of mutual understanding.