Tensions in the eastern Mediterranean

A region where energy security, global governance of the sea and seabed, and the roles of superpowers interconnect.

It seems that tensions between Substack and Twitter are developing, so to continue that theme, here is a case study of conflict to watch in the future.

[Now over 750 subscribers worldwide - thank you for your interest]

Introduction

In October 2020, a Turkish oil exploration vessel, the Oruc Reis, left the Turkish port of Kas, to search for offshore oil beneath the seabed between the Mediterranean islands of Cyprus and Crete, south of the Greek island of Kastellorizo [Figure 1]. This seemingly innocuous move greatly increased political tensions between several countries in the eastern Mediterranean – Turkey, Greece, Cyprus, Egypt, Syria, and Libya - and also caused stresses within the European Union (EU) and beyond.

These tensions were prompted by rivalry over future energy resources, though other broader factors played a significant role. These factors include rights to access resources beneath the seabed, and the governance of them as well as the waters above. The fact that several of these countries are members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), and therefore are meant to be military allies, makes resolution of the conflict challenging, especially for other leading countries in that alliance – the USA, France, and Germany.

So, what is the trouble all about?

Energy

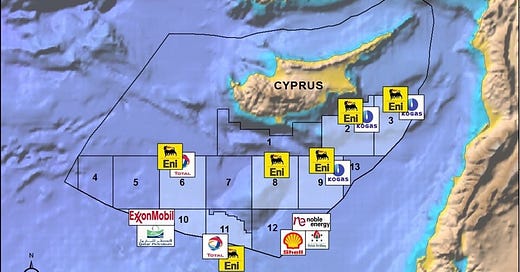

At one level it is all about natural gas. Significant gas fields have been found beneath the seabed in the eastern Mediterranean, around Cyprus and off the coasts of Egypt and Israel, and several countries, including Turkey, are actively exploring to develop them [Figure 1].

National rivalries, including disagreements over the delineation of maritime boundaries, have been resurrected.

Bi-lateral deals to recognise respective rights have also prompted rising tensions. For example, in 2019, Turkey signed a maritime accord with the Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA) and then began gas exploration in areas that Greece regards as its economic zone. Subsequently, in the summer of 2020, Greece and Egypt signed a maritime boundary agreement, prompting Turkish anger, and a renewed exploration effort (also by the Oruc Reis) and naval deployments.

While such energy exploration almost inevitably exacerbates tension and could provoke a regional air and naval arms race, joint regional action will be needed if the economic benefits of this gas are to be realised. Pipelines and other infrastructure must be created. The former must cross several countries' undersea ‘territory’ if they are to make landfall, say, for crucial European markets. A fledgling international infrastructure is being established for the new energy producers of the eastern Mediterranean basin and this could ultimately help to reduce tensions, maybe even offering a path to the resolution of the long-standing Cyprus geopolitical problem as well.

Figure 1

Cyprus

The island of Cyprus, a sovereign state and full member of the EU, has been the centre of dispute between Greece and Turkey ever since Turkish forces invaded the island in response to a Greek-backed military coup in 1974, with the subsequent unilateral declaration of a Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

This conflict builds upon a much longer history of enmity between the Greeks and the Turks going back to before the modern Turkish state was founded. Despite multiple diplomatic efforts - there were hopes that as Turkey came ever closer to EU membership, the Cyprus issue might be easier to resolve - it has proved intractable. However, with Turkey currently under the control of President Recep Erdogan, there is no prospect of it joining the EU. And the new tensions over energy have added another element to this very old dispute.

Turkey

Another important element of the issue is the assertive foreign policy currently being pursued by Turkey, which has been likened by some to a resurgence of the Ottoman Empire. The geographical horizons of President Erdogan have certainly expanded. Under his control, the country has also shifted from being a secular state to a more Islamist one in terms of its politics. Furthermore, the growing Turkish economy has become more dynamic helping it to establish the nation as a regional player, including establishing closer links with Russia, Iran, and Libya.

The Turkish government's ‘Blue Homeland’ doctrine envisages a greater maritime role for Turkey within what it regards as its own strategic waters. Some see their single-minded pursuit to protect its vital national interests as being overly aggressive, whereas others see such interests threatened - not least in Syria - where Turkey feels let down by many of its Western NATO allies, including the USA.

Military tensions have increased. The Oruc Reis was heavily protected by warships of the Turkish Navy. Another NATO country, France, became involved, siding with the Greeks. Also, a small number of F-16 warplanes from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) deployed to an air base on Crete for exercises with their Greek counterparts, although this was described as a routine deployment.

Libya

Like much of the Middle Eastern region, some say that political governance within Libya has become a proxy war, with various outside players lining up against each other. There are conflicting views between Turkey and the powerful actors of Egypt and the UAE. Turkey has intervened heavily on the side of the UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA), located in the west of the country, while the UAE and Egypt back the militias of General Khalifa Haftar which are based in the east of the country. Turkey and the UAE have conducted a drone war in Libya's skies, with the UAE operating its Chinese-supplied drones and the Turks deploying home-built armed drones of their own.

Differences over Libya have also soured relations between Turkey and France. Recently, there was a naval stand-off where Turkish warships intervened to stop the French Navy from intercepting a cargo vessel thought to be carrying weapons off the Libyan coast.

Amid the growing Greek-Turkish tensions, France despatched two warships and two maritime strike aircraft as a show of solidarity with Athens.

The USA

The USA has also sought to intervene in the area, albeit to a limited extent. Former President Trump suspended Turkey from further military aid (including the buying of F-15 warplanes) after its purchase of advanced Russian surface-to-air missiles. However, he did not criticise President Erdogan for his aggressive strategy in the region, and some observers stated his actions to be inconsistent. Consequently, in the absence of clear US action, Germany has sought to mediate between Greece and Turkey, particularly with France being more supportive of the Greeks.

Conclusion

The immediate cause of tensions in the Mediterranean may be energy-related but this only tells part of the story. There are both deep-seated and developing diplomatic strains which, combined, could erupt without warning. If ever a region needed crisis management, then it is the Eastern Mediterranean. But who exactly is to be the manager? And do the respective parties themselves want to be managed?

Update (April 2023)

For a region largely devoid of petroleum until a decade and a half ago, the East Mediterranean has now attracted several top international companies. For example, ADNOC (the Abu Dhabi National Oil Corporation) has recently teamed up with BP to buy an Israeli gas company (New Med Energy) which holds shares in both the Israeli and Cypriot gas fields. Similarly, UAE-based oil companies are keen to develop Israeli and Egyptian gas fields. Other TNCs involved include Eni (Italian), Kogas (South Korean), Shell and Exxon Mobil.

The gas fields in the eastern Mediterranean are estimated to contain 80 trillion cubic feet – more than the combined reserves of the EU, UK, and Norway. The question is how to get the gas to market. So far, the Israeli offshore gas supplies domestic needs, and some is sent to Egypt and Jordan. Cyprus has not yet managed to get a pipeline development started.

There are essentially three options to get the gas to Europe. First, send as much gas as possible to Egypt, liquefy it at the plants at Idku (near Alexandria) and Damietta, and then export by tanker. Second, build a new LNG facility, either floating, or onshore, probably in Cyprus. Third, build a pipeline, which could run under-sea to Crete and on to mainland Greece, then connect to south-east Europe and Italy.

So, what is holding up these projects, given the urgency driven by the war in Ukraine?

The politics of the area encompasses disputed borders, particularly with Turkey, the divided island of Cyprus, civil war in Syria, the government shambles in Beirut, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Secondly, there is a lack of urgency and interest from the countries of Europe, which are struggling to think and act strategically, particularly when it concerns fossil fuels. Furthermore, a pipeline or LNG plant which will operate more than 20 years seems problematic when the EU bloc is meant to reach net-zero carbon by 2050.