[The second of three posts on this area. I am grateful to subscriber David Kilham for the update on tourist numbers to Antarctica – to be found at https://iaato.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2022-2023-Tourists-By-Nationality-Vessel-Total.png ]

Antarctica provides an example of global governance. There has never been military conflict here or indeed any military activity. Unlike other remote and sparsely populated areas of the world such as the Pacific Ocean atolls, Siberia, and the interior of Australia, it has not been used for nuclear weapon testing. As the continent had no indigenous human population, 12 countries undertook an agreement in governance in the late 1950s. Over 60 years later, the 1959 Antarctic Treaty is a key element of global governance.

The treaty set out a vision of peaceful coexistence - 67 countries around the world agreed to work on national and transnational scientific programmes. Owing to cost and remoteness, only 12 countries have researched in Antarctica. These groups agreed to work collaboratively and independent of the political geographies of the rest of the world.

Territorial claims.

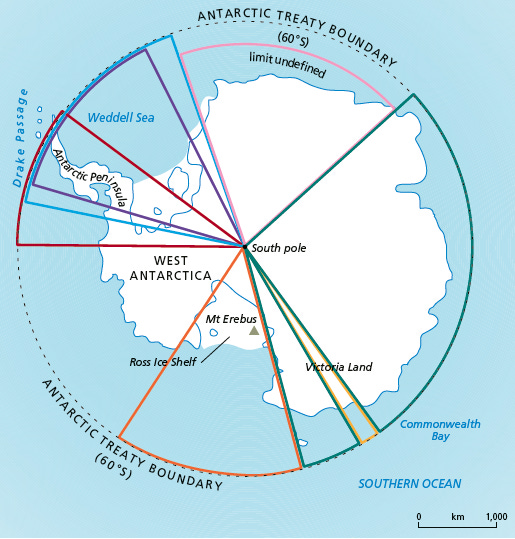

By the start of WW2, seven countries had made territorial claims to Antarctica, including Australia, the UK and Chile (Figure 1). One territorial sector, adjacent to the Pacific Ocean, was unclaimed. At the time, the Soviet Union and the USA did not recognise any of those territorial claims as legitimate.

To facilitate scientific research, all the claimant states had to accept that others could build research stations in ‘their’ territories. For example, the Soviet Union established a base in the Australian Antarctic Territory and notified the Australians that it was not leaving at the end of the programme of research. This was at the height of the Cold War, and the USA recognised that Antarctica’s disputed status had to be addressed in one way or another. Eventually a compromise was reached.

Figure 1. Territorial claims on Antarctica

What was agreed?

The Antarctic treaty declared that the continent and surrounding ocean (up to 60º south latitude) would be a zone of peace and cooperation. All military activities would be banned and claims to sovereignty suspended for the duration of the treaty. Nuclear testing was banned. The original signatories committed themselves to operate based on consensus so that all the parties had the same voting power.

This meant the two superpowers of the USA and the Soviet Union would have to work with other parties such as Belgium, South Africa, Japan, Norway, and New Zealand. The treaty allowed other countries to become signatories, but to become a voting member, they would have to demonstrate an ability to conduct ‘substantial scientific activity’ such as operating a scientific station in Antarctica.

The agreement was possible because of the time at which it happened - in 1961, before the Cuban Missile Crisis and the building of the Berlin Wall. It also occurred before further decolonisation by countries like Britain and France. This meant that the original signatories were able to stop India raising the ‘question of Antarctica’ at the UN.

Challenges in the 1980s

The Antarctic Treaty is also an example of a regional governance regime. It has a distinct area of application (all land, sea, and ice south of 60º S). Until the 1980s, the treaty parties were small in number and were eager to isolate themselves from global events. For example, they were content to work with South Africa under apartheid even though elsewhere that regime was being treated as illegitimate and subject to sanctions.

In the 1980s, the Antarctic attracted more global attention:

· new states such as India and China joined and had their own interests regarding the continent and its resources.

· parties to the treaty were negotiating new regimes for fisheries management and contemplating mining regulations.

· states from the global South complained in the UN General Assembly that a small group of countries was trying to exploit further this global commons.

Legal concepts such as common heritage of mankind provided new opportunities to reframe the Antarctic not as a natural laboratory for science but as a resource space that should be managed by the global community. The Antarctic Treaty parties decided to back away from a minerals convention and committed themselves to a new Protocol on Environmental Protection. Mining is banned.

Controversy

More recently, controversy has arisen between members of the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS). China and Russia favour greater exploitation of fishing resources. Other parties want to see more marine protected areas (MPAs), such as the one for the Ross Sea negotiated in December 2017, and biodiversity protection. Members are having to confront a reality made more complex by climate change, resource pressures, and a growing human footprint in the form of tourism, fishing, and science. There is also evidence of alien species invasion thanks to warming trends and human activity including shipping.

Protecting Antarctica is proving hard, especially with climate change. Anthropogenic climate change means that whatever happens in Antarctica cannot prevent further continental ice melt and warming of the Southern Ocean. Environmental groups such as the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC) are particularly unhappy that the Antarctic Treaty parties are not doing more to control tourism, to protect biological diversity and to establish further marine protected areas.

Sovereignty is disputed. The management of resources involves diplomacy and compromise. Meanwhile, claimant states such as Australia are worried that Russia and China are trying to increase their ‘rights’ in Antarctica. Recently, China was involved in a dispute about how to manage a remote area called Dome A – see here Dome Argus – Australian Antarctic Program (antarctica.gov.au). It demonstrated only too well that everything in Antarctica is politically sensitive.

The future?

Whatever the Antarctic Treaty parties do, they face a great deal of global scrutiny. Antarctica is recognised as integral to addressing the climate emergency. Global biodiversity targets require at least 10% of the world’s marine areas to be protected. In the 2020s there will be attempts to agree on additional MPAs in the Southern Ocean and Antarctica (to be covered in a subsequent Substack). But this will be difficult as nations such as China are resistant to restrictions on fishing.

A new UN convention on biological diversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ - high seas beyond the control of coastal states) will have consequences for the future management of the Southern Ocean. However, progress towards a global treaty for the high seas is slow as countries continue to argue about how to share resources, coordinate with fisheries-management groups, and commit to a global network of MPAs.

The 1959 treaty has a protocol that allows parties to call for a treaty review conference after 30 years of operation. So far no one has called for a review. But in an era of populism, it can’t be assumed that Antarctica is immune from more nationalist trends. If China, India, Russia, or the USA left the treaty then it is possible that the delicate compromises underpinning the management of Antarctica could fall apart.

The Ross Sea MPA can be reviewed after 35 years of enforcement (i.e. around 2053). In 2048, parties could ask for the provisions of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to be revisited. What would happen if treaty parties decided Antarctica’s resources no longer deserved protection, and a world undergoing further environmental change decided the northern Antarctic Peninsula was suitable for permanent human habitation? At present 55,000 tourists visit the Antarctic in any summer season and the permanent human population runs into the low thousands.

Antarctica may not be special for much longer.

Hi again, it’s me. Love this article, currently reading it in A level geography, again!!

#antarctica #oga #bigup #globalgovernance #exams

Also my teacher was wondering if you would come in and do an A level geography talk at our school. I can give you his details if you are interested.

#aqa #oga #geography4ever