[Recently I attended a Geography Review meeting within the grounds of Manchester University, close to the Devas Street HQ of the English exam board AQA. I used to visit this area regularly between the 1980s and early 2000s and each year I was struck by the changes that were taking place. That is still the case. The Oxford Road/University area of Manchester is a vibrant, multi-cultural, young, active area to walk through. It has prompted me to write about the larger area around the university that has in the past had a much different image – Moss Side.

PS. I have abandoned X (Twitter), and can now be found on BlueSky, where quite a few geographers have moved too. It’s much nicer there.]

Moss Side is an area up to 3km south of Manchester city centre. Its current population is approximately 20,000, many of which are students. In the past, Moss Side was often labelled as an area of crime, gangs, unemployment, deprivation, and dereliction.

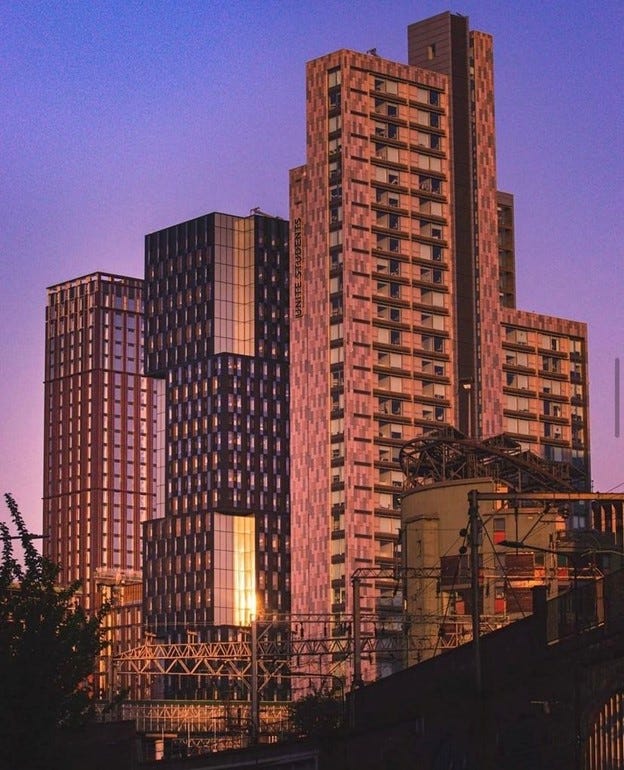

Student accommodation at Manchester University

Background

Moss Side was named after a large marsh that covered an area in south Manchester. In the novel Mary Barton, published in 1848, Elizabeth Gaskell described it as a rural idyll with a ‘deep clear pool’. By the late 1800s, Manchester’s cotton industry had expanded. The population of Moss Side grew from 151 in 1801 to almost 27,000 by 1901.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century terraced houses were built in the area, attracting many Irish and Polish migrants. Following WW2, migrants from the Indian subcontinent and the Caribbean then settled in the area. By the 1980s, Moss Side had become the hub of Manchester’s Afro-Caribbean community. During this time, gang violence increased, and the area became known as ‘gunchester’. In July 1981, mass riots broke out in the area fuelled by racial tensions, high levels of unemployment and economic recession. Since the mid-1990s, Moss Side has experienced substantial regeneration to address these issues.

State-led regeneration

In the 1990s, regeneration projects in and around Moss Side focused on physical regeneration, mostly housing, and were largely paid for with public funds. For example, the Moss Side and Hulme Partnership was established in 1997 by Manchester City Council to coordinate a 5-year programme of regeneration in these two neighbouring areas of Manchester. Projects included retail developments, improved housing and four new public parks costing about £400 million, paid for by the Single Regeneration Budget and the European Regional Development Fund.

The scheme pulled down a large housing development called the Hulme Horseshoes. The open-plan design of concrete walkways, lack of streets and poor lighting made these flats a crime hotspot. They were replaced with new houses and apartments designed to attract a variety of residents and eliminate crime. This development included a retail park, an ASDA supermarket, local community food stalls and a gym.

The Hulme Horseshoes

Developer-led regeneration

More recently, Manchester has been at the forefront of developer-led regeneration. This is funded by the private sector and based on the assumption that property-led regeneration can address the problems of inner-city neighbourhoods. Private sector investors aimed to build houses quickly so that they could recoup their investment through rental or sale of properties. Much of this property-led regeneration in Manchester provided homes (and high-rise student accommodation – see earlier photo) on brownfield sites close to the city centre, particularly along Deansgate.

Manchester’s skyline has been transformed with shiny metal and glass high-rise buildings (for example, Beetham Tower and Deansgate Square South Tower) that include facilities such as, bars, gyms, and restaurants.

Deansgate, Manchester

This type of development has been criticised for not providing access to transport, sufficient affordable housing, and schools. By 2020, there were over 80,000 people on the housing waiting list in Manchester. There are plans to create more affordable homes and social housing in inner-city areas like Moss Side.

Moss Side today

Moss Side is an area bustling with people and vitality. The area is attractive because:

· Housing is affordable: a two-bedroom property can be bought for £150-200k compared to a UK average of £250k.

· Transport links are good, with Oxford Road being one of the busiest bus routes in the city.

· Access to amenities includes healthcare (Manchester Royal Infirmary), recreation (the Aquatics Centre) and schools.

· The area is close to Manchester University, and many graduates settle there and work in the new industries of technology, biomedical sciences, and advanced manufacturing that are springing up in the area.

There are also challenges:

· Private landlords have bought up properties to rent to the large student population. Hence, there is a shortage of housing for locally-born households.

· The area is still dominated by relatively deprived, single, transient people renting low-cost accommodation, including many students.

Maine Road football stadium

In 2003, Manchester City Football Club moved from Maine Road, Moss Side to a new, larger site in east Manchester (the Etihad stadium). This created an opportunity for new housing in the area. The developer Lowry Homes was given a loan from the government to build over 400 houses and apartments (including social housing) involving eco-friendly technology, and a new primary school.

Despite these positives, there were some losses to the area too. Manchester City football club was a source of local association, and income. When the regular influx of 35,000 fans stopped, local shops and services were forced to close. The new homes were meant to attract long-term residents, but many properties have now been let by landlords taking advantage of Manchester University’s growing popularity.

What next? Developer-led regeneration has not been entirely successful. Could the new post-Covid way of thinking about ‘Culture-led regeneration’ be the answer for further regenerating Moss Side? The sheer diversity of the area could be seen as a positive.

[I have written about post-Covid urban regeneration in the forthcoming January edition of Geography Review]

Great detail David . Well done !